Headstrong Above All the Rest: An Interview with Joel Krass

When I set out to work on my second book, Majorlabelland and Assorted Oddities, one of the strangest cases of major label interference I’ve come across was of Headstrong. An alternative metal band from Canada, the band hit the big time when they were invited to perform on the short-lived USA Network show “Farmclub.com” that ended up with them scoring a deal with RCA. The band were at loggerheads with the label over practically everything and less than five months after the release of their album, with a song on the radio and out on the road supporting Tommy Lee, the label pulled the rug out from under them and by 2003, the band was over, with a lot of bad memories left behind. I’ve talked to guitarist Joel Krass several times about the band but this was the first time we had a definitive, all-encompassing interview about the band’s history. Krass pulled no punches and the result is one of the most striking and hard-hitting interviews I’ve conducted. Enjoy and afterwards, go on YouTube and dig into a very aurally pleasing band.

Headstrong Discography:

Headstrong (RCA, 2002)

Notable Tracks: Adriana, Swing Harder

Pete Crigler: How did you become interested in music?

Joel Krass: I recognize this

question is a trap to lull me into a sense of security so I provide deeper answers

to later, more important questions, but sure, let’s get a leg well stuck so we

can start to chew it off. We all become interested in music the same way –

programming. We are quickly attuned to music as a mnemonic device, or command

for calm or obedience; something akin to how a baby penguin can seek its

mother’s chirp or squawk amongst the Antarctic din. Even if we are happy and we

know it, we must clap our hands. Soon,

this leaves the realm of useful development and becomes a tool to manipulate and

divide us at worst and inspire, motivate or comfort us at best. But what leaves

it all when we become tied to the wheel as mass-market listeners is our

awareness that we are being played with in an entirely new way.

For readers interested in my personal

past, I was put into music lessons by young parents in the 70s who saw the

value in music as a way to engage the brain and develop creativity, discipline

and talent. Real romantic post-Vietnam stuff. By 18 months I was in a

Suzuki-esque program in our little town and was exposed to a more experiential

music education than rigorous study. Early education is not such church pew

sternness as exploration and no wrong answers. It’s about listening, touching,

feeling, being moved and letting the brain connect the dots no matter the end.

So, one could argue I didn’t even have a choice to ever become interested in

music. As a toddler and early youth, I often came into lessons with a bloody

lip from tripping on the sidewalk as I bolted from the car to escape having to

even go. My parents worked hard, and we were modest people, so I regret not

recognizing the sacrifices they were making early in their lives, but again, I

wasn’t even 2 fucking years old at this point. I am learning to try to give

myself a break here and there.

I studied away half-heartedly until

my teens and then I was really inspired by Jon Cohen (my future bandmate) to

believe in music as not just a thing I listened to, but I could be a part of.

Jon and I spent all our spare time begging for rides to our respective cities

so we could hang out and beaver away at playing our favourite metal songs,

4-tracking, learning production skills and eventually writing. By the time we

were 15, we were playing shows for high-school Amnesty benefits and were even employed

by the city to busk acoustically in the town of Port Dalhousie, which was

likely the best job I ever had looking back at the purity of the task. As

border-town kids, our friends in Buffalo would invite us to do some recording

over there at the SUNY campus occasionally and it was surreal in how easy it

was to even have that kind of cooperation given the distributive and secure

nature of society in the aftermath of 9/11. Jon was always so generous with his

time and knowledge with me and he was truly a great friend. We had a little duo

called ‘Three Singing Guys’ (the third singing guy was you) it was fun and dumb

but we weren’t all that bad. I will always be grateful for his nigh-endless

contribution to our success, which has been perpetually unrecognized and

under-celebrated. Jon had been told at a very early age that he had to leave

home ‘to learn the value of a dollar’, and through all of that for a teenager,

he never lost his compass, his drive or his ethic. He is the one you should be

interviewing.

For my music education, I continued with my lessons here and there and with a great instructor named Steve Kostyk, the main axeman for the legendary Polka King Walter Ostanek. Steve had all the chop and knowledge across so many disciplines and genres, but alas I was just another shitty teen who didn’t practice enough to get the benefit of what he was really trying to tell me. He tried really, really hard to recognize that I didn’t want to just do what everyone my age wanted to do, and from him, I learned to love players like George Benson, Joe Pass and others.

Pete: How did bomb32 come together

and what was the Canadian music scene like at the time?

Joel: Soon, because I was the

youngest, my best friend left town to go to London, Ontario to study music

production at the best program in the Province (and probably the country) -

Fanshawe College. At the time, this program was headed up by legendary producer

Jack Richardson. Jon developed further in his skills and I raced to join him as

fast as I could a year later. I wanted a university experience however, I

really lacked the formal training for a music program despite my origins, so I

studied Classical Studies at the University of Western Ontario, which I enjoyed

very much.

Here, roaming the halls of my residence, I met Brian and Matt who shared a similar bond of being musical partners through their years at summer camp. We were fast friends, and inevitably they met Jon and saw the road the way I did. As I was the glue that held us together, I was a defacto leader and while I really tried to lead from behind, I recognized that we would need some kind of structure if we were ever to get past the ‘just write a bunch of shit’ aesthetic. The residence was big, some 1250 people, and any in-gym performance brought hundreds of people no matter what we were doing at the time, so it was a very fertile proving ground to get confident enough to start looking outwards. The edge that young people have is that built-in community that comes from education. As adults, even with some kind of network we are still relatively isolated and audiences are more atomized than ever.

Pete: Tell me about those early bomb32 recordings.

Joel: One thing I think that was

interesting about our really early days was how many incarnations of ourselves

we had before we settled on bomb32. We would practice for a while in the early

months, play a club show, and then change our name and format and do it all

over again. We held retail jobs and such to fund our rehearsal space and basic

promotion like every college kid does, but it was an almost hilarious pursuit

of futility to go from concept to polish to performance to instant abandonment

like that. We did several cycles of this from The Angry Briefcase Men, to

Clever Hans and I’m sure some that I forget. We would do dumb stuff like trivia

and giveaways of shitty things like restaurant menus we had pilfered from

around town. Shitty dumb teen stuff, but what can I say.

Once we really recognized ourselves

as a band, and settled on bomb32 as a concept, things become semi-serious.

Digital recordings were not possible yet (believe it or not) and recording to

tape required studio time, let alone the $200 a reel for the fucking tape. Our

little retail jobs were not gonna give us the juice to record anything good

without us going hungry. So, as one does, we strategized. We sought out every

reputable battle of the bands in our region that offered time as a 1st

prize and we competed. And lo, we won every fucking time no matter where or

when. We didn’t take a second for granted, and we would show up to record so

prepared, engineers thought we were nuts. Before we even booked time, we would

already have track sheets and people literally would play their parts in front

of the group solo so we could be confident they weren’t going to fuck it up at

an hourly rate, and in doing so we could tighten up any obvious problems before

they went to tape. We were so insane we would practice blindfolded at times so

we could learn to not look at our fucking hands and be better at engaging

audiences. I wish I were even kidding. We were nuts. We lived in a tiny house

and set up the basement with some rudimentary soundproofing and workshopped

incessantly. I’m sure the guys would agree these were the real best days, long

before we had ever stepped foot into the majors.

As you’d expect, not every Battle

yielded the most glorious reward, and so early recordings came from basement

studios with local part-time engineers, one lovely guy Mark Prokopiou, had a

great old house and some iso rooms and a control room in his dungeon. It was a

great set up for demos and pre-pro, but the reel to reel would conk out all the

time, and he would just exhale loudly, stare at the ceiling and yell ‘everyone

needs to get the fuck out right now’ every time it would happen. Somehow, we

still managed to get demos done. The Brain record was done here, and it was the

start of something meaningful to us at least, but utterly meaningless in the

expanse of the void.

Eventually, we recognized that you

cap-out on what you can do with just an engineer, and so we sought out Dan

Brodbeck to produce us. Dan was just a few years older than us, but wildly

talented and just a fucking absolute joy to be with. Our first encounter went

the same as the others: we showed up with a fucking IMPOSSIBLE workload and

very little time to do it, but because we were organized and prepared we would

somehow finish an absurd 10 songs and mixes in 2.5 days and some such shit. I

don’t know how Dan put up with it to be honest, but I don’t remember him ever

being afraid of hard work. He is a gift to the universe and I am so grateful

for him.

Most of our early demos with Dan didn’t get compiled into a release because we were learning the value of being our own worst critics. We knew the importance of a first impression and didn’t want to release anything but the best work we could possibly do. For the first time, we had real production value through Dan, and we took his time very seriously from then on out. Bulk recording sessions became pre-pro demo dumps which we then reviewed harshly to pull out the best material. With only the A+ material remaining and the carcass of the others picked clean, we would return to Dan to attack a few singles to attract real attention. After a few years of developing some trust in each other, it started to work.

Pete: How did the band come to appear on Farm Club and do you think it helped the band?

Joel: The usual story, band gets

some conviction, grows out of their pond and moves to bigger marketplace thinking

they are ready for bigger things. You know, we used to write our heroes and

send them our recordings asking for advice or help, some of them would even

write back. The one message that stuck with me most was from Helmet’s Henry

Bogdan. He sent us a postcard from Germany with a big red train on the front

and just wrote ‘Make enough noise and they come to you.’ It was the best advice

we ever got. So we made some noise.

Soon, seeing that we were attracting

crowds in reputable venues, people began sniffing about for the crumbs of what

money they thought we were making. Truly, there was none. Every dollar we

earned we poured into the band, either for recording, rehearsing, logistics or

promotion. We literally tithed ourselves from our new city office jobs to pay

for shit. We each could not fucking wait to quit the dogshit of 9-5 and were

happy to dump our pockets out into the project in the hopes it would get us

there. It was never easy to get these gigs; no one knew who we were, but I

would diligently call up venues like Lee’s Palace and ask for the booker and

make my case. I’ll never forget him saying ‘Do you think I walk out of here to

a golden limousine and go sleep in a diamond castle?’ when I asked for a gig,

but by the end of the call we had one.

To your question, Farm Club to my

knowledge came out from some cigar-room favour trading with management after we

signed to Romanline/Deep South. There was some tag about ‘we uploaded music and

got a million votes’ but I think most people aren’t naïve enough to think the

music industry is a democracy. Farm Club was an amazing experience, both a

dream and a nightmare at times, but there is no question it helped the band,

though not in any way people might think.

Truthfully, we left Farm Club with nothing, and it wasn’t until a year later that it would have an impact on our lives. One day we were invited/summoned to the BMG building in Times Square to meet with David Bendeth about signing to RCA. We’d met David before, as we were being courted semi-seriously by a few labels and had developed some buzz in our hometown. After what was a disastrous meeting, we basically resolved ourselves to go back home empty-handed rather than compromise our principles or our membership. The day was put clearly in the Loss column and we wandered back to our low-rent NY hotel to drink the free bottle of wine they gave us before we contemplated coming up with the cash for the gas to drive home. Later that night, after watching some wrestling, our episode of FarmClub came serendipitously across the screen and we had an offer in the morning. Luck is truly the residue of design. That said, the deal was far from closed that day, and the saga long continued well after, but FarmClub was in the rear view. Still, I’d like to see the broadcast again, because our actual performance was such a shit-show, I’d be interested to see how they cut around it.

Pete: At what point did the name to change to Headstrong and how did it come about?

Joel: On signing, and like most

other things about us, the label hated the name bomb32. Somehow, even though we

had settled on it in the late 90s, EVERYONE was a word# now. So, as was our

custom, we phoenix/ash death-cycled the brand as we had so many times in the

past. New fans saw this as a sell-out compromise, but anyone who knew our roots

knew we literally did this shit all the fucking time in the old days. We built

it and blew it up, built it and blew it up, shampoo, rinse, blow it up.

People might not know, that even

though the four of us were the same, it was an entirely different band. Bomb32 was a five piece, and Headstrong was a

four. B32 was about being kids in college finding themselves, Headstrong was a

group of intelligent men (at least at times if that is even possible) with a

clear message that without responsibility we choose annihilation.

The name itself came from a new-age exercise where I had the guys put out every fucking name they could think of without any rejection or criticism on a list, and then we all voted in cycles to narrow it down. Matt came up with that name, and eventually through distillation it invariably won. Something about that moment was special, because it revealed how really Matt had all this potential that was not yet supernova.

Pete: How did the band get signed to RCA and how do you feel about it now?

Joel: I kind of covered that above,

we made some noise, attracted industry and did what every band does: sign the

best deal they can. What maybe made us special is that we weren’t afraid to say

no, so when a bad deal came our way, we refused to be desperate enough to take

it. RCA was interesting and we did have some advocates there, particularly in

the radio department (Bill Burrs most notably) and certainly we learned a lot

about music itself from David, but it was never easy. After the courting the

label was instantly combative and conversations often quickly turned to

ultimatums, which by nature we never responded well to.

Now? It was a thing we could never control so much as exist in. We did our best and I’m just glad we didn’t let them tear us apart personally, as we saw them do with so many bands who were groups of friends at the time. Lord fucking knows they tried from day one. You give a fairly exhaustive list of bands in a similar state in your book and I can confirm that most of those groups were encouraged to cycle out members because it made the label’s job easier. “Do you want to be a band or do you want to be friends”, was the attitude, but for anyone intelligent, life is never so binary.

Pete: What caused Humpartzoomian to leave and what was it like bringing in Jon?

Joel: I’m so sorry to even read

this. We didn’t bring Jon in, JON INVENTED THE BAND. Jon was the engine of our

creativity since inception, and for me personally since I was 10 years

old. Rich, God love him, was just a kid

we had audition for bass when were putting the band together in the 90s. He wasn’t part of any of the childhood soul

bonds and he was younger than us still thinking about how he wanted to live his

life. Eventually he decided he wanted to be a psychiatrist, so he didn’t make

the move to Toronto with us. I hope he eventually did reach his professional

goals and I wish him well and am grateful for the years we spent together.

Jon on the other hand, was the LEAD SINGER in bomb32, and we had a different set up, where Jon and Matt would switch off rhythm guitar and lead vocals all the time. They rapped together for certain songs, and I did harmonies and played the main guitar. The reason Jon began playing bass exclusively is that for a year after moving to the city, we simply couldn’t find anyone any good, and one day he threw up his hands and said, ‘fuck I’ll figure it out.’ And figure it out he did. It was not easy move to come off the mic for him, but it is not fucking easy to intonate to a booming rock bass on a noisy live stage, and the show was tighter without all the swap in swap out stuff, so we just went with it. It was a decision we should have revisited because Jon was fucking good, and a lot of the lyrics people really love are his creation. I really failed him in not re-opening the discussion about getting him back to lead vocals at least at times, but Matt was shooting the lights out and everything was working, however fragile.

Pete: What was it like making the album with David Bendeth and Dan Brodbeck?

Joel: These are two fundamentally

different questions. Dan is a magical person, full of skill and humour and

earnestness, where as David is a master manipulator who weaponizes psychology

but is also steeped in real experience. Both want the same outcome, the best

record possible as they perceive that goal. Two roads to get there, one bumpier

than the other to be sure. We’d worked with Dan for much of our developmental

years and we fought extremely hard to do the record with him. We knew that we

could trust him to make sure we made the record WE wanted and not the record

THEY wanted. The RCA plan was the usual two-weeks in LA for $100k and someone

swaps your parts out when you leave the studio.

We were firm about locking in with Dan for months to do things right,

and we blocked out EMAC studios for 3 months at $30k (Canadian) to do it. The

compromise that won the label over was that we’d spend a literal fuck ton to mix

it with a ‘guy’ in LA. It was actually a great formula for everyone, and we

loved working with JJP (Jack Joseph Puig, producer/mixer) in Ocean Way so much too. David on the other hand, while

not always combative, would fly in late when we were too exhausted to mount any

resistance and start tearing songs apart. He wasn’t always wrong, and we

learned a lot about being a band from him, but there wasn’t much trust there;

and that is literally everything to me.

What I’m most grateful for is that the process gave some spotlight to Dan with the US majors, and because he so undeniably extraordinary it helped (in some small part) to lead to really great things for him, and I’m glad we were able to do anything at all to help him be as successful as he deserves to be. Not to say that he needed us, quite the contrary, but I think making that record was special and timely for everyone involved and if there was a real hero in the room, it was undoubtedly Dan Brodbeck.

Pete: What was song writing like within the band?

Joel: Usually, but not exclusively, we’d all be writing away on our own time and bring a bag of riffs or ideas to practice and start putting them together into skeletons of songs. Lots of big flip paper with dumb riff names and song structures to keep everyone on track and we’d just massage and knead them into tunes that worked. About 95% of what came to practise didn’t make it out. Quality control was an overriding doctrine. Sometimes, a start-to-finish song would come in, but that was really rare. And it was never a whole shebang lyrics, rhythms and all. For the most part, when I was writing, if I felt like I had something really good on the line, I would seek out Brian to help reel it in, because things just don’t sound real until you put drums to them. But everyone’s process was different, and we were merciless critics. It’s actually amazing that anyone came back day after day at 12 noon to do it again after being eviscerated by their closest friends the day before. And yet.

Pete: How did Adriana come to be the song picked to go to radio?

Joel: God I wish it weren’t. Leading

with a ballad for a new band in a new territory is idiotic and the song was not

really representative of our greater sound. I will take credit for most of this

disaster because it was my riffs and arrangement both musically and vocally

that got the track from inception to finish line. I was kicking around the

music overnight at the hotel while we were tracking, and it just took legs. Our

strategy from the get-go was to have some solid foundations for a record, but

enough time in studio to get fired up to write as well. Adriana almost never

got finished because Matt and David finally had enough of butting heads over

his vocal style, and while they were screaming at each-other over an

international phone call, I just went to work trying to re-work Matt’s chorus

more melodically. Of course, with Dan at the console, it went very well and no

one argued that the song wasn’t better for it.

Ultimately, I think the label

argument for Adriana to be the single was that it had the most crossover

potential. For us, it was new and we always liked our newer stuff because so

little survived the writing process. When you abort every slightly misshapen

child, I guess you treasure the ones you keep. For me, deep down I *knew* it

wasn’t the right call for a 1st single, but in my vanity, I guess I

liked the idea that it was *my* song that everyone liked. Truly, there were no

*my* songs, every song was ours in every way, and as a leader I failed my team

in that moment not advocating for ‘Do What You Feel Like’ to be the

single.

Pete: Where do you think the band fit in with what was going on in Canada at the time?

Joel: Well, we were quickly dubbed a

RATM clone, a Tool clone, a Limp Bizkit clone or Linkin Park clone everywhere

we went. People would love to tell us we were ripping off bands we’d never even

heard of, most notably Snot (who in retrospect were great, but they didn’t

penetrate Canada so there was no influence there). So we fit in well enough,

but we weren’t really recognized as being particularly good or original. The

usual this-meets-that in every possible form, so much like everything else, yet

you could describe it any way you wanted, and the comparisons were always

somewhat derisive and diminishing when brandished by our critics. Canada, as

every American knows is full of very very talented people that just have to

cross to border to be successful. Sadly enough though, Canada never offered us

a deal and we were kind of punished for going south when it was over. We took

the only deal we were offered, and we tried to work with Canadians whenever we

could, we fought to record in Canada, but we never felt the love that other

Canadian artists in our peer group felt, to be perfectly honest. Yes, local

radio was good to us, but we could feel the behind-the-back chatter and almost

relief from some people here that we had failed, because they could tell

themselves at night that they were right to not sign us in the first place. We

weren’t the ones that got away so much as the bullet dodged.

This is more to do with the industry than the music scene of course, amongst our network of bands, we felt tremendous love and support from The Salads, Breach of Trust (fucking amazing records btw), Zuul’s Evil Disco and many more bands that I am forgetting here. One thing about Canada as opposed to the states is that that USA Haze culture is less pronounced here. On every tour in the US, your headliner would feel almost obligated to fuck with you, in a sick pay-it-forward-it-was-hard-for-me-it-better-be-hard-for-you. I don’t want to get into specifics, because it would embarrass some of those acts (I hope), but they don’t do it out of pure malice as much as conditioning. On the Canadian side, band culture is so much more ‘we are part of something bigger’ and ‘hey, I love what you do, let’s do something together’ so much as the American music is a contest and it’s ‘time-for-your-initiation-hazing-ritual.’ Suffice to say, my phone does not ring from the American bands we met along the way, checking in to see how we’re holding up. Everyone was more or less glad to see us go, sometimes out of seeming jealousy for what they thought was an easy road to for us to get as far as we did.

Pete: How would you define the term success in regards to the band?

Joel: Well, we’re all still friends

and we made the record we wanted so that to me is success. Everything else is

nice-to-have, that was need-to-have. No one remembers us and no one should, any

time I post a song online it goes unliked, if I share an anecdote I am met with

‘cool story bro, I bet everybody clapped’ and yeah, it’s disheartening, but we

were a pre-internet band and the world is different now that everyone is a

star.

Yes, we charted, yes we toured, it was often great but always hard work and none of it came easy or without sacrifice. If you believe in what you do, hard work is success in itself.

Pete: What happened with the Tommy Lee tour?

Joel: God knows, guy probably hated us, lord knows his fans and his crew fucking did. His band and he were nice enough, but god it sucked hearing his crowd bitch at us every single night to get off stage before we even started because they were so thirsty to see him. Maybe we sucked. I’d never really seen or heard our show from that side of the stage in 9-years, so how would I know. It wouldn’t surprise me to see RCA post our deal memo in an r/instantregret subreddit, to be honest. Who can say? In hindsight we were DOA at RCA, so maybe they just felt a cash squeeze from Napster creeping in and cut the fat. Maybe I had one too many confrontations with people trying to fuck over my guys, and people were sick of me not backing down. But I will never regret anything I ever did or said to protect my guys. That was my fucking job and I did it. Every dollar we ever spent of our advance or gear money was soundly invested to ensure the next stage of the project could even potentially materialize, not that any one at the label or in the periphery would even try to recognize that.

Pete: How long afterwards was the band dropped and what was your reaction?

Joel: When it was clear we were

going to be on the road for the better part of 18-months, we gave up our

apartments and put our stuff on the curb because we couldn’t afford Toronto

rents on empty rooms. I was crashing on my sister’s couch, and within a day or

two, Bendeth called (and not management curiously) to tell us we were dropped. He

told me no one at the label stuck up for us and no one wanted to do the second

record, himself included. So as one does, I loudly told him to fuck himself and

hung up. Everyone in our support staff ghosted us (management, agency, etc) and

we were on our own again.

It was fucking demoralizing beyond belief, because we really, really, really believed in the record and it is a good fucking record, even more so considering it was our FIRST major release. To not get the option for #2 was a kick in the groin so hard that our nuts popped out of our eyesockets. My reaction was to get to fucken work making sure we could try to find another deal before the RCA marketing spend went cold. Guys were depressed as shit, and I was too undeveloped as a leader to recognize mental health issues then, so me whipping everyone to get to work was not as effective a tactic as I’d hoped, but it did yield the subject of your next question.

Pete: Tell me about the recording of demos like How White; were they supposed to be tracks for a 2nd record?

Joel: Again, lots of pre-pro in the

rehearsal room birthed two tracks we thought had a chance to secure us another

deal, maybe in Canada if possible. We had been kicking around parts of certain

songs to get ready for what we thought was record #2, but soon that was out the

window, and we were back to making polished singles to shop for a new deal. That’s

when things took a turn for the worse and we got a leg drop from the top rope

in the form of a lawsuit from a former manger.

Resources got diverted to legal

defense, even though the suit was baseless and ultimately dropped, the idea of

having any money left over for a new record that could compete in the US majors

was fucking over and no one had some office job they hated to tithe off the

cash to do it. We were cooked. We spent what we had left to finish what became

a hail-mary demo session to do False Start and How White, and I do really love

them. We worked with Dan again, and he really gave us break on it because he

was with us through the whole thing and he knew just what a shitshow our

signing was. Again, all gratitude to him, he’s a truly wonderful and generous

person.

But no deal came. The industry decided that RCA regretted signing us and other labels gave themselves a pat on the back for not putting an offer forth. We had one kind of half-baked offer floated from an indy, but it wasn’t all that solid. As the saying goes, “when you’re hot you’re hot, when you’re cold, you freeze in the dark.”

Pete: What ultimately ended up causing the band’s breakup?

Joel: In a word, me. In my failing to recognize that we all suffer idiosyncratically, and that you can’t just compel people out of depression by overloading them with work, I got frustrated that the iron was going cold. The industry was failing around us because of P2P and that $20 billion that came out of the business wasn’t ever coming back, so the entire proposition of being a musician became a loser almost overnight. It was a hard decision and I regret not having the wherewithal to just take an extended break or find a more nuanced solution, but we had not arrived at our pinnacle without a truly endless amount of hard work that only got harder all the time. Foot off the gas was never our doctrine, but man, the guys were fucking gutted by how we were going out, and it was almost like a shovel to the face of the band was the humane thing to do because I lacked the finesse to bring them back to form. Obviously I was hurting as bad as anyone else, but I didn’t want to admit I was bleeding because I felt that more than anything we needed to push on. But you can’t make a dead man march and work wasn’t the answer to a team that was utterly exhausted. Live and learn, it’s a miracle anyone still talks to me.

Pete: What were you up to after the split?

Joel: After some flailing and wallowing I started a dot-com with another friend and went on with a new life. I had to sell my gear to pay taxes so, a new band was out of the question until I had any money at all. We were successful for a time, until we inevitably fell out in part because my business partner started reading Tony Robbins books and became an insufferable prick. The Canadian gov’t made a quick Christmas time change in the criminal code to outlaw our little website, and I was back to zero again. This time I put all my chips into going back to school and just my luck I graduated into a global financial collapse. Typical 10-year boom-bust cycle that has been my story since I was out of high school.

Pete: What are you and everyone currently doing?

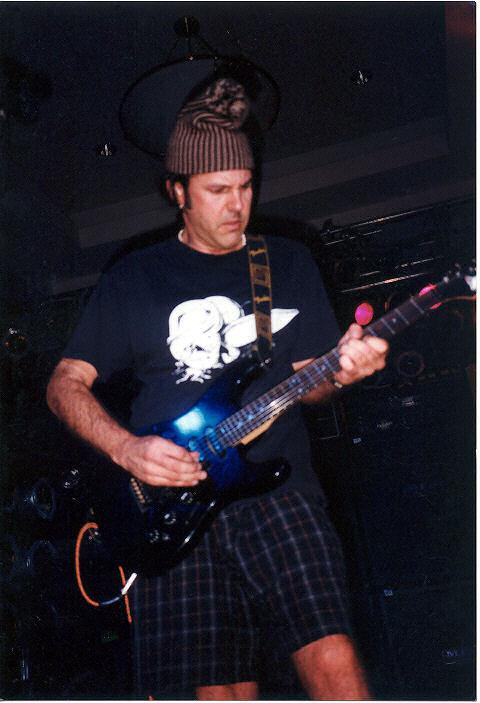

Joel: I perform with a little blues

trio, nothing serious, just a torch-bearer band, we carry some old tunes as far

as we can until we fall down for the next band to pick them up. Bar stuff, you

know.

Matt is in Early Childhood education

and has returned to writing. His new work is great and it shows a

thoughtfulness and acumen which reveals that he was likely the most talented of

us all along.

Jon is a high-school teacher, and

releases a punk record every year he records on his own every year from a very

small sunroom in a very modest condo. Great fun stuff that really speaks to his

roots as a teen living on his own.

Brian snapped back into the workforce faster than anyone after the split and is a Director at Entertainment One’s Canadian office last time I checked but he could have since moved up from there.

Pete: What was it like playing those brief reunion shows?

Joel: It was nice to feel a piece of that youth and hope that had long since oxidized from time. We were happy to see Matt starting to have a family, and we spend so little time as a foursome nowadays, it was recognized as a rare and precious thing by all. I think we played ok, but it wasn’t a Headstrong show, but rather a mystery gig kind of thing (we did a bunch of Kyuss tunes and some Allman Brothers for example) so it wasn’t meant to be all that well attended outside of close friends and family. That’s how we wanted it. Darren Dumas from the Salads was instrumental in getting us a night at the Hard Rock Café, which was a place we had loved to gig at in our heyday. Again, so grateful for him and others like him.

Pete: Do you feel the band was snuffed out before they got to achieve their true potential?

Joel: Well, yes, but I think that’s

true of a lot of bands in that era. You can’t suck $20 billion dollars out of

an industry without leaving some bodies behind. The creative-destruction from

technology and absolute disregard for artists that music fans were willing to

wreak on the business was just insurmountable.

Maybe it still is; it’s not my problem anymore. Everyone just kind of

takes a piece of you without even asking and when you finally get a good look

at the remains, there is no you left in it.

Ultimately, people say I’m just a sour grapes kind of guy, but truly they know nothing about me or our experience over the 9-years as a band, and I’ve long since realized I can’t stop people from entrenching uninformed opinions. Everyone does a quick wiki and says ‘they’re a one record, one hit wonder’, but it was a decade of our lives that no one knows anything about, and they don’t need to. It doesn’t matter.

Pete: What do you hope the band’s legacy will be?

Joel: You know, I stand by my answer from the 2012 question that you

asked me in your book ‘Majorlabelland and other Oddities’, I would like you to

reprint it here if you would, but given the current state of things in the

world, the events of January 6th, the years of birtherism and

corruption to follow under president shitstain, and the blind hate and lies

that are being exported from the United States around the globe, I suppose I

have more to say about it. This should come as no surprise given the fact that

our entire career was based on an answer to a question that everyone quickly

wished they hadn’t asked. I guess here I go again.

You know, I’m not trying to say that it was some kind of punishment to

be signed. It was an adventure to be sure, and while it was a lean

operation on the road (fans thought we were roadies who just let a line check

get out of hand some of the time) we didn’t starve, and for some-to-most of the

time, people that worked for and with us like Amy Cox or any of the former

management were working really hard, so I’m always glad to see they landed

right. RCA DID release our record, they DID provide reasonable support, they

DID let us do most of what we wanted aesthetically (as steered by their staff),

Bendeth DID have a human side where he would put you up at his place, he WAS

more mentor than torturer, bands DID welcome us and not all threw cold cuts at

us while we performed and other such dumb shit, people DID show us some empathy

for a while at least after we totally wrecked on the mountainside and we were

back on the road the next day with a new van and trailer, etc, etc. There are

lots of great memories and lots of smile miles. It was NOT ALL BAD, TRY HARD TO

DO IT YOURSELF IF THAT’S YOU WANT! This is not a boo-hoo I had a record deal

story, I loved playing with the guys and I always will, I don’t regret a second

of it and they never let me down. Look, I’ve been solo quarantine for 11 months

since coronavirus started, it’s getting a little gloomy, February is not as

exciting as it once was. I think I feel the way I do now because of the way

that whole thing started was kind of a ‘would you kill one or two of your

friendships to sign’ and ‘how’s a last minute lowball’ sound, so you already

had to be put in that situation from the get-go. You see through a different

lens after that, and for the people that said ‘yes’, a lot of those bands

didn’t get their second option either and a 2nd record is

literally everything if I haven’t been clear on that. People always say

they’d LOVE TO BE IN OUR SITUATION, but it started on the foot of having look

hard at your closest family members and saying ‘ok, we’ll give up grandma for a

1/10 of the turkey’ without even asking her. If you are the person to say

yes to that, dude. People are free to be assholes to people they trust

and who trust them, they are also free to make hard decisions for the self,

that just didn’t work for us individually or as a whole which was only

competitive BECAUSE of the trust that we had. Getting pulled off before the end

of concert season on your first cycle and denied option 2 is akin to blowing up

on the launch pad. Your first record is like being throwing naked into a

freezing (or boiling?! Who can tell at these temperatures?) kind of river, and

you are swiftly carried away. What you learn is that you can’t really get

off to regroup, you hug onto a log and learn to do everything you used to as

you navigate it. Welcome to the jungle, you’re a fucking houseboat.

Truly,

there is no legacy to our little band. Even those professionals (with the

exception of Dan) that worked with us have quickly erased us from their

ledgers, no matter how much they expressed interest in the project at the time.

JJP doesn’t list our album in his discography, our video does not appear in

Thomas Mignone’s credits, I’m sure Warren Entner would give you a blank stare

legitimately not even recognizing our names if you asked him about us. You

can’t even find our Billboard ranking without an exhaustive search on the

wayback machine. Such is the business. Once branded a failure (or perhaps a

pariah), people distance themselves from you.

But I stand by our work, and I am proud that we fought so hard to hone a

message that is clearly anti-fascist, condemns extremism and corruption in all

forms, and begs listeners to pursue some thoughtful introspection and basic

responsibility.

Author's Note: Joel

also talked about the band’s legacy in a 2012 interview for Majorlabelland and asked that his thoughts about the band be included: “The band’s

legacy? Honestly, I don’t care. We lacked the required notions of narcissism

and vanity to be successful in the pop-music industry, so if we are forgotten,

I am fine with that. I would rather die unknown and with humility than have

been known for rapacious and wanton self-promotion above the conditions of the

nation and her citizens. The music is out there, we long since lost control of

it. My only hope is this is not co-opted by those who want to use it to sell an

idea’s that are destructive and self-interested.”

Comments

Post a Comment