Straight Outta Norfolk, VA: An Interview with Buck Down of Combine

Discography:

Norfolk, VA (Caroline, 1995)

The History of American Rock and Roll (Caroline, 1996)

Combine were an indie/punk outfit from Norfolk, VA. Though they managed to have some great indie success, both nationally and in the Tidewater region, they never hit the big time, though they deserved it richly. The band released two national albums on Caroline Records and were in the process of making a third when they fell apart. You can’t obtain their records on most digital platforms but they do have a Bandcamp (https://combine1.bandcamp.com/) where the music can be heard in all its glorious remastered form. I had the great pleasure of conducting an interview with the band’s singer/guitarist Buck Down, then known as Brian Pafumi and he spoke about the band’s history and where they fit in with the rest of the storied Virginia music scene.

Pete: When did you first become interested in music?

Buck Down: Probably somewhere around 4 years old – I was convinced that there were tiny musicians inside of the radio performing the music I heard coming out of the speakers, which frankly isn’t much more fantastic than how radio actually works. I have been on a virtually non-stop personal mission to unravel how music works and why ever since.

Pete: Tell me about how Combine came together and what it was like developing the band’s sound?

Buck: Xavier and I were working together at a screen printing factory called American Silk Screen just behind Cogan’s. At some point both of us ended up in between bands at roughly the same time (1991) and decided to get together after work and make some noise. I think Xavier picked up John for another project that didn’t quite gel.

The first 30 minutes we were in a room together we wrote the song “Javaman” (which would later appear on our first record as well as every demo we did prior). It’s probably the most singularly defining song in our catalog, as It pretty much exemplifies all of our reflexive musical tendencies in just under 3 minutes.

At that point, Xavier and I spent all day every day in that shop listening the highly repetitive, extremely rhythmic grind of automatic screen printing machines all day, which without a doubt was reflected in our music. I can point to multiple instances in our music where the part is simply randomly mashing notes at an arbitrary position on the neck of the guitar and churning 16th notes across all 6 strings as aggressively as possible in a manner that sounded remarkably similar to the churn of the machines we were surrounded by all day.

Pete: Was the local scene supportive of a band such as yours and was the band able to find its own place?

Buck:

Norfolk in the early 1990s was a magical place for local rock n roll bands. The

reality was that most nationally touring indie rock acts weren’t going to blow

their weekend shows on a tertiary market like Norfolk, which meant that the

best 2 nights, Friday and Saturday were always open for local acts to play any

one of 4 or 5 decent live venues in the neighborhood - which made for a

great local scene.

There was an available pool of maybe 30 or 40 musicians in town that were incredibly incestuously linked. If you were a person in a band in Norfolk in that time and walked into Kings Head Inn on a Saturday night, the odds that you either had been in a band with, worked with, lived with or at least shared a practice place with at least one of the other people on stage on any given weekend night was functionally one out of one. As a result – we were all remarkably supportive of each other. Which isn’t to say that there wasn’t at least some in group / out group social stratification, but you could overcome it by simply writing 7 or 8 good songs.

Pete: How did Staplegun

Records come into play and what happened with the initial recordings?

Buck: We self-financed a cassette EP called “More Friendlier” in the first year or so we were together. In the pre-internet days, traveling indie bands served as a sort of pony express for the material culture of our time, which was basically hastily (if not poorly) recorded demo tapes, Xerox fanzines, etc. We opened up for enough “big” bands at the outset that we would shower with our tapes and t-shirts that they in turn Johnny Appleseeded to other towns.

Staplegun was a little label out of Plano TX that was run out of some kids bedroom, that I’m fairly certain was in his parent’s house. Staplegun had made a decent enough ripple by putting out a compilation of recognizable indie bands all doing REM covers, which apparently gave them enough money to sign a band – which ended up being us somehow.

Kris (the label owner) had a friend in NYC that was starting out as a producer

and had a gig working at a small studio in the Village. We got enough money to

rent a van and go up to New York. Jason (the producer) was living with a lady

that happened to not only be willing to let us stay at her tiny place, but also

happened to have a pretty decent job working for Polygram records and knew a

lot of people. This was the beginning of a very strange bedfellows love affair

between New York City and Combine.

We made an EP called “Meat is Dinner” which as I remember was basically just

better recorded versions of what was on our “More Friendlier” tape. This was

also the first time we had ever set foot in a “real” recording studio (Green

Street Studios) that had gold and platinum records on the wall. We always took

what we did VERY seriously – and this was the first point at which it felt like

the work we put in paid real dividends, and it informed our work ethic from

that point on.

Unfortunately – Staplegun couldn’t get it together to actually manufacture and distribute the record we made. The good news was we were starting to get some attention and buzz in New York, and Staplegun did the right thing and put some effort into selling us.

Pete: At what point did Caroline come in and sign the band and do you feel it was a good move?

Buck:

My memory is a little fuzzy around this time – but essentially we somehow

transitioned from the idea of an EP with Staplegun to the idea of recording a

whole album back in Virginia. My suspicion is that Staplegun had doubled down

and decided that if the goal was to sell us to a larger label – a whole record

would be a better pricetag than a half-finished EP. We had just signed with

Girly Action Media and Management at that point and I’m fairly certain Felice

(Ecker – our manager) had some firm interest. I think we were one of Girly

Action’s first signings – and they were no joke. They would go on to work with

hundreds of bands you’ve heard of.

We were absolutely thrilled at the prospect of going to Caroline, not the least

of which because at that point Caroline was being run by Lyle Preslar – who was

the guitarist from Minor Threat – which to some old school Virginia punks of a

certain age was like meeting one of the Beatles.

Caroline was a great home. At that point they were humming – and there was a

veritable army of people working our records. Honestly the greatest casualty of

the streaming model is how many unsung music promotion jobs went away. The

people that called radio stations, and sent posters to local record stores,

etc. That’s what separated the haves from the have nots in the indie music

industry back then.

Pete: How was it recording with Robert Poss?

Buck: We actually recorded with Robert in Virginia, at Larry Carr’s studio out in Chesapeake. It was fantastic. Robert was (still is) one of my guitar heroes, and the presence of sort of angular repetitious interlocking parts in our music definitely got lifted from Band of Susans. It’s impossible to overstate how much I learned from Robert vis a vis how to record an album, and how to make bitchin’ guitar sounds. Him and Wharton Tiers were my Yoda and Obi Wan Kenobi, respectively. What I learned from them is why and how I am a producer now, and I am eternally in their debt.

Pete: How would you describe the amount of success or

lack thereof throughout the band’s history?

Buck: We had pretty realistic, and it turns out, very achievable goals. Namely

– we wanted to get signed by a decent independent label, and we wanted to tour,

so by that standard – we were wildly successful. We spent about 5 years on the

road nearly non-stop, and we played damn near every city you’ve ever heard of

and quite a few you probably haven’t. We got to do cool feather-in-the-hat shit

like play sell out shows at CBGBs a couple times and eventually achieved my

teenage dream of playing the Boathouse. I can’t think of anything we wanted to

do that we didn’t, shy of not getting to do a 3rd record with

Caroline.

Pete: What was touring like on the indie circuit during the mid ‘90s?

Buck: Absolutely magic. It’s hard to overstate how impossibly cool it was to be roaming the country in your mid 20’s with your best friends on someone else’s dime in a rock n’ roll band. It was beyond even Jack Kerouac’s wildest dreams. In some ways – it ruined me for life. Once your day job is to go town to town blasting your own music in the greatest dive bars in America for enthusiastic crowds – it’s sort of hard to go back to punching a clock in the traditional sense of the word. I’m 50 now and take enormous pride that I’ve managed to pay my way this whole time with art.

Pete: What was the overall theme behind the second album and what was it like recording with Wharton Tiers?

Buck:

One of the things they neglect to tell you in Rock School is that while you

have your entire life to write your first record, you only have about a year or

so to write the second one – and the catch is that entire year you are pretty

much perpetually on tour, and the stretches of a few weeks between tours is

usually not your most creative arc. Most of it is spent trying to salvage all

the relationships that have been stretched to the breaking point by your always

being gone.

Wharton had always been on our bucket list. We were enormous fans of almost

everything he had ever done, and being that he was Paul’s (from the Waxing

Poetics) uncle we felt he was pretty gettable.

Wharton was amazing on every level, I don’t know if you could have made a

better producer for Combine in a laboratory. We had already gotten him to do

the final mix on the first record (Norfolk, VA) and we were pretty hell bent on

doing the second with him.

We had a pretty decent budget from Caroline. The first record did pretty well,

was very well reviewed and everyone felt like we were on the brink of something

big. Which was a lot of pressure to be under.

Like I said – we had been on the road pretty much nonstop, and most of what

became our second record was written at soundchecks. We definitely had gotten

into the idea of doing free form stuff in our live shows at that point so there

were a few things that came out of those as well.

Thematically – we basically wrote what we knew – which at that point were songs

about being in an indie band at a kind of strange time in the music industry.

We passed The History of American Rock ‘n’ Roll as a “punk rock opera”

as it was definitely attempting to be a concept record, in so far as we were

capable of making one. In hindsight – it was probably a side effect of writing

a bunch of songs in a compressed period of time that kept everything so

contiguous. I think it actually aged pretty well all told.

It is not a completely unfair assessment to say that our gasp wasn’t as far as

our reach. While I don’t think we could have made a better record under the

circumstances, I don’t think it had the same tautness the first one did. It was

a victim in some ways of some of the excess we were enjoying. Anytime you see a

punk band putting a string section in one of their numbers you can rest assured

they probably have started taking themselves way too seriously.

Pete: What happened with the third record?

Buck: It never saw the light of day. Things unraveled really fast with

Caroline, and we were also personally unraveling as well, in particular John

and I. We were definitely the last people to find out that Caroline was being

sold. It felt like almost everything fell apart at once. We were dropped, we

wrecked our van, and ended up having to make the painful decision to let John

go in what seemed like a month. It was probably longer – but it felt almost

overnight

Xavier and I were pretty determined to die with our boots on, so we ended up

hiring Danny Magee to play drums and then we went on a songwriting frenzy. At

that point – (Waxing Poetics guitarist) Paul Johnson was living in Brooklyn and

had a pretty decent studio in his basement. We trekked up north once again to

record with yet another member of the Teirs / Johnson clan. Had we done a 4th record,

we would likely have needed to scour through their nieces.

To this day – I don’t even personally own a copy of that recording, and can

safely say I haven’t heard it in at least 20+ years. I honestly have no idea if

it was any good or not. I do remember getting Gordon Bradley to play a little

on it, and in my memory, he did a couple really stellar takes.

Pete: Did Caroline drop the band as a result of

wanting to move in a more electronica direction?

Buck: Caroline was a subsidiary of Virgin Records. At that point in human

history – “alternative” music was still sort of a fringe part of the mainstream

music industry. Rock radio was still dominated by “classic rock” stations

playing Stairway to Heaven and China Grove for the

billionth time.

Every

major had gobbled up an indie because that was where the energy seemed to lie,

but none of them really understood the first thing about how that culture

worked, much less the numbers. Ultimately – the irony was that the earning

potential of all of those small labels was being kneecapped by the same larger

labels that owned them vis a vis all the glass ceilings they had installed to

protect the market share of their super big acts. Also – none of these bigger

labels understood how to jam econo, so ultimately bands like ours were

railroaded into what would have been avoidable levels of debt if they had been

run on smaller margins.

At this point – the electronic music underground was just starting to

proliferate, and Caroline had a decent piece of it. When EMI bought the label

and looked at the balance sheet – it was obvious that touring indie rock bands

were basically a filament for the churn of money that it took to keep them

going – whereas one guy at home on his computer could deliver a finished

electronica record without very requiring expensive studio time, to say nothing

of the cost of touring. In the end – in the new paradigm of the label, just

about all the active touring bands, including us, were dropped fairly

unceremoniously for what I imagine were very unsentimental business reasons,

while the more cost-efficient electronica got to stay.

Pete: Did the band attempt to find another deal and when did the band throw in the towel?

Buck:

I mean we must have. It’s been so long ago, I can’t remember what the gap was

between when we lost our Caroline deal and when Girly Action (our management)

wandered off – but I can’t imagine it was long. At this point – a lot of bigger

labels were getting gun shy about moving up underground bands – not the least

of which because a lot of those bands were plagued by drug problems that made

them patently unreliable.

With

the advent of the “X” stations (ie: commercial alternative) labels wanted bands

that were safer and more manageable and less likely to miss shows because

someone was out wandering a seedy neighborhood in a strange town on tour trying

to fend off junksickness. That’s how you ended up with bands like Hootie and

the Blowfish and Matchbox 20 and shit. Unfortunately – we didn’t have the squeaky

cleanest reputation, and I am positive that factored into making it difficult

to find us a new home.

Hard drugs were ubiquitous in Norfolk at that period and were definitely

burning their way through all the local bands. Almost every band had a problem

child or 2 in it, and not all of them lived. Life expectancy for a Norfolk

guitarist was plunging and my name was definitely moving up the dead pool.

The longer we weren’t on tour – the more self-destructive I became. I lucked

out that Wharton hooked me up with a band on Interscope called Unwritten Law

that was in need of a tour manager / FOH soundguy – which got me out of Norfolk

for a month or two and away from the dead end of the local drug culture. By the

end of the tour I had gotten solidly clean – and the last thing I wanted to do

was go back to Norfolk and backslide into addiction again – so I took an offer

to run front of house sound at The Roxy in Los Angeles I had gotten on the UL

tour. The idea was just going to put me in LA for a few months. That was 23

years ago and I never managed to come back, which was pretty much the whimper

that Combine ended with.

Pete: What is everyone currently up to?

Buck:

Xavier is playing in a band called Song of Praise (https://www.facebook.com/songofpraisenfk/) and has a nice

little cottage industry hand-painting motorcycle helmets (which by the way are

utterly fantastic.).

Johnny moved up near Baltimore and I think may be sitting in on a couple gigs

with The PLRS (former members of Buttsteak).

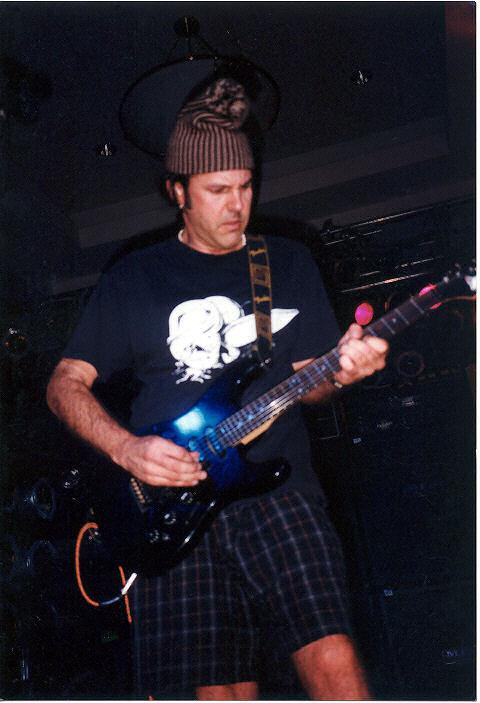

I’m still out in Los Angeles running a little project recording studio and

putting out solo records at the moment (https://buckaedown.bandcamp.com)

Pete: What was it like reuniting and performing at the Veer Awards?

Buck:

Incredible. The three of us have remained close. We have a 3 way chat on Facebook

messenger that we are all on pretty much daily. The one thing that never

changed was how ferociously we love each other, and how incredibly protective

of each other all of us are to this day. Being back on stage together was

absolutely intoxicating, but almost better was going to rehearsals together

every night for a week. When we first started playing together – we rehearsed

pretty much 7 days a week. There really isn’t a lot of things I can think of

that feel more safe than being loud as fuck in a tiny room with those guys and

no one else around.

The Veer Awards was sort of a perfect context to get back together, and getting the Lifetime Achievement Award actually affected me more profoundly than I thought it would. It was an incredible homecoming and I think it really tied up some loose ends that had been hanging for far too long.

Pete: Is there potential for more shows in the future?

Buck:

I certainly hope so. As long as all 3 of us are still alive there’s always a

chance. Shit – I’d be surprised if we weren’t making ungodly racket in

some senior facility multipurpose room in 30 years.

I feel like we have at least one more proper record and tour in us – it’s just

figuring out how to make it with all 3 of us being in different cities. I

imagine it will require all going on an extended writing and recording vacation

somewhere – which actually sounds like a lot of fun.

Pete: How representative do you feel the band is when it comes to the Virginia music scene?

Buck: I have no idea where we fit in now – but at the time – we were dutifully lifting some element or 2 off of each good Norfolk band at the time. I think we always saw ourselves as aspiring to be the most prototypical Norfolk band of all time. I would love it if that is how we’re remembered.

Pete: What do you hope the band’s legacy will be?

Buck:

I think we want to be remembered as the local boys that went out into the

outside world and did good. We certainly were blessed with arguably the most high-profile

deal that any band from Norfolk ever got, and I’d like to think we represented

our gritty little home town well in the process. I have no idea how many people

saw Combine and then decided to start their own band, but I’d say every one of

those people represent a singular metric of our real success.

I

think we at least proved that a working class band out of a southern tertiary

market can break nationally if you love each other and what you do enough to

work hard on it.

More

than anything else – I think our legacy is each other. The bond between the

three of us is one of the deepest emotional connections I think any of us has

ever experienced, and has proven to stand the test of time. It eclipses

anything we’ve ever done artistically by a long shot. The memories of being

together cut loose out on the open road in this state of almost iridescent

freedom and youth will be burned in my psyche till the day I die. I’ve managed

to keep myself in the business of show this whole time and since traveled the

world playing music – but nothing compares to your first run at it – and I

couldn’t have found 2 better guys to do it with in this or a hundred lifetimes.

I’ll treasure it forever.

Comments

Post a Comment