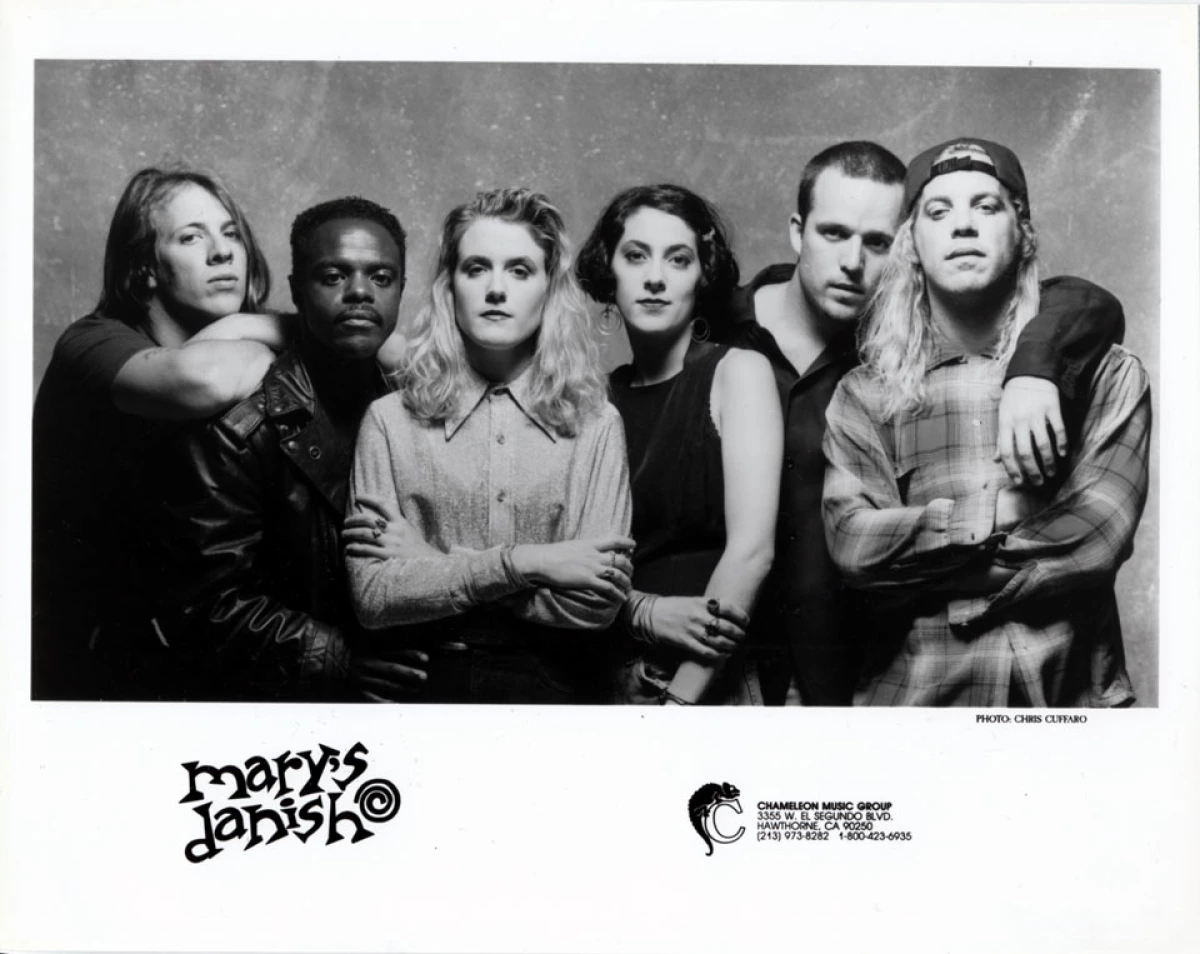

Millions of Peaches, Peaches for Me!: A Chat with Chris Ballew of the Presidents of the United States of America

Discography:

The Presidents of the United States of America (POPLlama/Columbia, 1995)

II (Columbia,

1996)

Pure Frosting

(Columbia, 1998)

Freaked Out and

Small (MusicBlitz, 2000)

Love Everybody (PUSA

Music, 2004)

These Are the Good

Times People (Fugitive Recordings, 2008)

Kudos to You! (PUSA Music, 2014)

Popular Tracks: Lump, Peaches, Kitty, Mach 5, Volcano, Video Killed

the Radio Star

One of the most unlikely success stories of the decade, the Presidents of the USA offered a respite from the typical Seattle gloom and doom/I hate myself and want to die ethos that had been popular for so long. Bright, relatively happy and lo-fi as hell, the band quickly became a smash thanks to essential novelties like “Lump” and “Peaches.” The alternative bubble affected them more than anyone and they disbanded quickly in 1998, only to reunite like eight months later to continue making great music until 2016. The band’s music is still remembered as a nice alternative to what else was on the radio at the time and the fact that music fans like to have fun from time to time. Frontman/bassist Chris Ballew chatted by phone with me about four years ago and it was one of the most invigorating interviews I've ever done.

Pete Crigler: When did you become interested in playing music?

Chris Ballew: I became interested in playing music definitely when I was super, super tiny, when I was two and a half, I got Sgt. Pepper when it came out in 1967. My brother, my way older brother had gave it to my parents who didn't understand it, and I inherited it, and fell deeply in love with it, and that's when I knew that's what I wanted to do on a deep, deep level. At the age of four I started piano lessons, and I was actually getting groomed to be a concert pianist that I didn't really like the, what's the word? The regiment. It was kind of intense. So anyway, I really was very, very young. It was very clear that I wanted to swim in those waters that the Beatles were swimming in with that album.

Pete: Before the band started you worked with Beck and Mark Sandman, how did that come about?

Chris: Well Mark was first. I met Mark in 1990 I think, '89 maybe, and one time we tried to remember how we met and we couldn't, we just seem to have known each other for ever. But he kinda took me under his wing. That relationship was definitely a kind of mentor, mentee type relationship. He let me live with him. I was kind of a penniless vagabond weirdo musician, and somehow he just decided to help me out, and he's a very private person, but he let me live with him, we had a band together called Super Group where we improvised all the songs, and he turned me on to the two string, and he played a two string slide on a bass. He had a guitar version that you could fret with your fingers that he was experimenting with and when I picked that up everything just fell into place. And I just felt like this is it, this is what I've been looking for. And I still have that guitar. He cryptically mailed it to me a year before he died.

It had shown up unannounced at my house in a big box, and had a note that just said, "You're in charge of this now."

Yeah it was amazing. So yeah, he really allowed me ... That band we had together was very important for me because he was very cool, and centered, and grounded, and I was just this freaky little guy bouncing around being whackadoodle. And he allowed me to ... He didn't tell me to calm down, or to change my thing, or whatever, he just let me be weird. And that's when I discovered that… But yeah, I sort of learned a little bit of ... I mean eventually his aesthetic settled in many years after he passed away even. What he was trying to turn me onto back then took time to settle in to my palette, my musical palette. But it did settle in eventually. He's super important. He's like my musical father in a way. Beck was a situation where he and a friend of mine shared a publisher, and she, this friend, called me up and said, "Hey, I know this guy Beck and he needs musicians for his band. He's gonna go on tour. He just got signed. You and he are totally cut from the same cloth. You should audition for the band." And I kind of ignored it, and then she called back and insisted, and so I met him when he came to Seattle, and immediately just totally fell head over heels in love with his songs, his voice, his imagery, the surreality of quilts of weirdness that his lyrics would weave, and so he and I just hit if off right of the bat and ...I ended up in his band for the very first two tours that he ever did.

I don't know what

they were there to hear because the experience was really interesting. It was

like Beck did not like that song. He tossed it off before they went and got

burritos one day and it became a hit, so I immediately got lesson number one,

which is don't release anything you don't totally love because it might become

a hit.

Really, being with

Beck was like going to fame school. It was like I got to stand next to the eye

of the storm and watch him navigate it. I was the only band member not from LA,

so he let me live with him. We wrote a couple songs together, and played around

with a four track, and drove all over LA eating food and doing radio shows and

little in-stores together. We were a little bit of a duo for a bit there in

some capacity.

We just talked

about his transformation, what he was going through, and figuring out how to

navigate the waters of going from drinking and drugging and sleeping in a box

on a hillside above the video store where he worked to dining with record

company executives and putting a band together to go on tour. It was a very

disorienting time for him.

Pete: How did you come to meet Jason and Dave? I know Jason was playing with Love Battery for a long time.

Chris: Yeah, he was playing in Love Battery. Dave and I went to high school together. He was a grade above me, and he was always the cool kid with the guitar playing songs. Super popular, and I was a bit more of a bowl-haircut dork. But eventually he and I started hanging out and playing songs together, and we started an acoustic duo called The Dukes of Pop. We played at open mics just kind of for fun, but we had good songs, and we had a good chemistry going on. Then I went off to college, and he went off to college, and we didn't see each other for a long time. Finally, I ended up back in Seattle after living in Boston and New York in the early 90s, like '93. I called Dave up, and we started goofing around with this new two- and three-string guitar thing that I learned from Mark Sandman. Dave was willing to play three strings, so that was cool.

We used to have no

drummer, and we played through the same amplifier when we started out.

The thing that

made that fun was it was like ... I think from an audience perspective, we

played as if we were a giant rock band, in some ways. We had all the attitude

of a band that was huge, but we were two guys on a Tuesday night opening up for

some other band at a club where there were only 50 people or something. I think

the audience empathized with us. They're like, "Oh, look at those two

little dorks up there trying to rock. I want to put them in my pocket. They're

so cute."

Then Jason saw us

eventually. We plodded along as a duo for a bit, and then we added a drummer, a

friend of mine, Dave Thiele.

Yeah, we added

Dave, but then Jason saw us with Dave and was like, "Oh, you guys need a

real drummer." Because Dave's not a real drummer, or he wasn't then. Jason

joined up, and we maintained that kind of dorky, three guys trying to rock

thing because we made Jason play a tiny drum kit with no cymbals, just a little

hi-hat and maybe a tiny splash, you know, a little thing.

We maintained that

dinky-ness, and that was my favorite time of the band, right after Jason joined

until we signed and got huge, because I found it compelling to be that dorky

little trio trying to rock. I think that chemistry is really interesting, and

funny, and fun. The once we got signed, we got new amps, and we got a bigger

drum kit, and we got a real sound guy. Pretty soon, we were just ... I'm not

saying we were just a regular rock band because we were singing very unusual

songs, and we still had dynamics and stuff.

I could see the

writing on the wall. We were just turning into ... If you stand up in front 50

people, it's way more fun than if you stand up in front of 50,000 because in

front of 50,000 you can't really goof around.

Pete: This is like the common question, what was the scene like in Seattle? Did you think it helped the band in terms of getting signed and things like that?

Chris: Absolutely. When Soundgarden got signed, really, because they were the first ones, and then Nirvana…They were the pioneers.

Yeah, because

Soundgarden got signed and Nirvana was blowing up, clubs were full of people

because everybody was like what's next?

Anyway, it was

cool because there was a built-in crowd, and we pushed that to the limit.

That's kind of how we tipped over into success was we were like, "Well,

we're playing on a Tuesday night and the place is full, and Saturday night the

place is full. Wednesday night, the place is full. Let's just see how many

times we can play and see if people stop coming."

We tried that, and

people just kept coming and kept coming and kept coming. It was great. It was

very fertile soil.

Pete: What was it like making the early seven inches? Were those before Jason came into the picture?

Chris: No, he was in the picture. We went and recorded at a place called Laundry Room where Dave Grohl made the first Foo Fighters record, and Barrett recorded us. We made a little cassette tape out of that, and we had extra songs, and we decided to do some seven-inch deals with little labels. Those were the old days when you had to wait around for a major label to really make a record that would go anywhere. Plus, that really wasn't our intention. I distinctly have a really vivid memory of Dave and I getting into his car, he's getting in the driver's side and I'm getting in the passenger side, and over the top of the car he says to me, "You know, if some major label wanted to come along and pay us a whole bunch of money to play these songs all over the world, I'd go. I'd do it. I'd sign up."

And I said,

"me too", while thinking in my mind and not saying it out loud, are

you nuts? Have you heard our songs? Nobody's going to want to ... We're not

doing this for that. We're doing this for fun just to make life interesting.

My attitude about

the whole thing was always like I just want an accessory to my already awesome

life, which was not successful in the traditional sense but definitely

successful in that I just had friends, and we had beers, and we smoked pot, and

we played Frisbee, and we ran around, and we played music in the evenings. It

was pretty damned good.

Pete: What was it like making that first record with Conrad? He was already legendary at that point.

Chris: Yeah. That was great. He was real sparse with comments. Really, it was just like is Conrad dancing around in the control room or bobbing his head and smiling or not. If he wasn't, we were like, oh, this isn't right. And if he was, then we're like, oh, that's cool. He likes it so it must be good.

It was funny. He

was like a barometer for whether we were hitting the mark or not. I realize now

with perspective, I think what made The Presidents work was that we had an

innocence and we had innuendo, and we mixed the two together.

We had very

innocent imagery, and we also had sexuality and stuff like that. We put those

two in the blender, so when that chemistry was firing, Conrad was smiling,

basically.

Then four of the

songs from the Laundry Room demo tape made it onto the record, and then we did

another nine with Conrad. That's when Kim ... Kim Thayil from Soundgarden was

an early adopter of The Presidents, and he would come to our shows and was

super into it. I ended up hanging out with him a lot, and he played guitar on

Naked and Famous. He's like, "I want to be on the record. Let me be on the

record, though."

We had this

section in Naked and Famous where it was supposed to be like a really crazy

noodle-y, heavy metal guitar solo, so we're like, well, perfect. That's you.

Pete: When did Columbia come around? How do you feel about signing to them now?

Chris: Oh, fine. It was great. Late in the summer of, what was it, '94 I guess? We played ... Oh, gosh. Dave is better with dates, but I think it was the summer of '94, we played an ASCAP showcase. I didn't know this, but the place was full of major label people because there was a big festival in town called Bumbershoot.

They were there to

check out bands and stuff, and it was a hotbed of the next big thing. We had

seven major labels at least at the show, and I didn't know that, thank

goodness, because I would have probably been nervous. But I just went up, and

we did our usual dorky, shamble-y performance. Then the next day, literally the

next day, we had seven major label offers, and we had to quickly put on

business hats and figure out what the hell was going on.

Dave became our

business guy. He read Donald Passman's book about the music industry, which is

like the bible. Jason became late night PR. He would take label people and

party with them until they fell down. And I was creative. I would come up with

more songs that those guys would help me arrange. We really early identified

our strengths and were like, okay, team. We were a three-headed monster, like

let's all get strong at what we're best at.

When it came time

to finally sign with Columbia ... We got down to Columbia and Maverick, which

was Madonna's label. And we had a very awesome business meeting with Madonna in

her L.A. offices, and she was great. She totally understood the balance of us

caring about our craft but not appearing to care at all. She has lots of

insight, and she actually saved me a lot of future heartache by taking me aside

after the meeting and saying, "You know, if you sign with me or not, I'm

going to tell you something. You guys are fun and funny, so you're not ever going

to get any respect for your craft, for the work you put into your songs out

there in the world, so don't wait around for it. Just do your thing and don't

pay attention to anything else."

It turned out to

be true, and she saved me a lot of grief, so that was nice. We took that away

from the Maverick meeting, but then we ended up signing with Columbia. They had

this guy, Mark Ghuneim, I'm not sure how to spell his name, but G-U-N-I-M-E, I

think. I remember him as being like Dennis Leary on crack, jumping up ...

He was their

internet guy, and the internet was new, right? He was like, "We're going

to pioneer this amazing internet space," and blah blah blah, so we were

really wowed by him and signed with Columbia. We ended up licensing our record

to them for seven years, so they didn't get the record, because we made it

without them. It existed, and we knew it was good. We knew it made people

happy. We're like, "We won't take a big advance or anything."

Nothing, actually. We too very little, enough to pay our rent and stuff like

that, but in exchange we will license you the album and then we'll get it back,

so we own that record now and have for a long time.

Really, we lost

nothing by signing with Columbia.

We only gained a

foothold in the bitter stage of music, so it was great. That was, I think, a

lot of Dave and Jason's smarts and acumen got us into that favorable position,

so kudos to them.

Pete: Here's the obligatory question. What were the inspirations for stuff like Mach 5, Peaches, Lump, stuff like that, you're quote, unquote, hits?

Chris: Yeah, all kind of different ... Lump was a fragment on a little micro cassette recorder that I had. I used to, back in those days, fill up a little micro cassettes with ideas, fragments. Anything I thought of, I would record it, and then I would listen to them while I cleaned my room or did the dishes and kind of wait for something that grabbed my attention. Lump was on there, and I do not remember making it up at all. But that's definitely my voice singing that song. It was just the chorus, and then I slapped the verses on, ran across the street, and borrowed a four-track from my neighbor, coincidentally, who was Lori Goldston who played cello with Nirvana, which is weird.

Anyway, she lent

me a four-track, and I quickly recorded that song, a demo. It was real mellow

and kind of lounge-y, and then the band rocked it out. That was a classic,

almost like That Thing You Do, that song. "It's too slow. Play it faster.

It's a hit!"

Then Peaches is a

little tricky to talk about because there were drugs involved.

I was on a drug

called LSD, and I was waiting for a girl I had a crush on, actually the girl

that ended up introducing me to Beck, to come home to her house, and she lived

... this is the weirdest scene. She lived in an industrial part of Cambridge,

Boston, low, gray, machine shops and stuff. Except her house had a picket

fence, and a yard, and it was canary yellow, Victorian house with a peach tree

in the yard.

And so, to

extenuate the drug experience, I was sitting in this, you know, Tweety

Bird-yellow house yard smashing peaches in my hands, waiting for this girl to

come home. And she never showed up. So I put all my frustration in the song,

all my desperate needs in the song.

So that's kind of

that one. And Dave came along. I had verse, chorus, verse, chorus, and Dave

came along and did the ending part. That's all Dave.

And Mach 5 was the

true story of how I ... just sort of describing how when I was a kid, I used to

love to create elaborate situations for my Matchbox cars, where I would take

them outside, and I'd take a hammer and smash them, and light them on fire, and

pretend there was just a giant accident.

Yeah. And I don't

know why it went ... I think I went with Mach 5 because it wasn't the Mach 5

from Speed Racer, but I had a car that had a 5 on it and said the word

"Mach" on the door. And I actually kept it. All those years, I had

this one car.

Pete: What was success like? How did everyone react to it? Good or bad?

Chris: All good. All good. Yeah. It was really nice to ... you know, having had the experience with Beck that I had, and the time I logged in with Mark Sandman, and Madonna's advice. And you know, some perspective and some age, you know, I was 29, 30 years old.

I didn't put all

my eggs in the basket, in that basket, as far as being ... as far as depending

on it for a sense of well-being and happiness. I immediately knew that when we

got signed, it was like metaphorically walking through that doorway into the

room where you think all the cool shit's going down, and all the cool people

are, right?

And so we get led

into that room, and immediately, the first thing I see is another door to

another smaller room. So, in my mind, I'm like, "Oh, this is never gonna

end." Trying to get into the next room, and the next door, it's like a MC

Escher design, never gonna stop. I will always be striving. And my first

impulse was, "No. I don't want that. I don't want to have my potential

sense of self and success and well-being connected to unforeseen circumstances

like getting airplay on a radio station, or people liking our new hit, or

whatever, our new single."

So I really

recoiled, but I kind of kept going because I'm in a band, and it's democratic,

and also, you know, we were riding a pony that was pooping gold bricks. So you

don't really get off of gold brick pooping pony until the pony stops pooping

gold bricks. And then you're like, "Pony. I'm gonna kill you."

So yeah, I rode

the pony. And then, you know, we eventually ... Yeah, well, anyway. We'll get

to that. But that's kind of like the ... you know, feeling of that was

outwardly, everything's great. Inwardly, I definitely had a big red flag up.

Like, "Okay. I'm gonna proceed with extreme caution."

Pete: What was it like being nominated for Grammy's?

Chris: Oh, super thrilling. Yeah, my phone lit up that day. It was all these, you know, friends and family, and then press calling and stuff like that. So, yeah. We were nominated for two, album of the year and song of the year or something. And two years in a row. And we lost to The Beatles and Nirvana. I don't feel too bad about losing to those people. That's okay. But to be in a category with The Beatles and Nirvana, that was great. You know, so. Yeah.

Pete: Did you guys feel any sort of backlash?

Chris: Backlash.

No. Mm-mm. No. Because we weren't trying to prove anything. You know? We were

just three guys having fun playing silly songs. I mean, what kind of backlash

could there be? It's like, we kind of exploded so fast that I don't think the

scene had time to feel like they owned, you know, or anything. It wasn't like

The Beatles leading the cavern and everybody crying.

It was like, you

know, we still played in Seattle, and we just played everywhere else, too. So

yeah, no. I didn't detect any backlash. I mean, we were made fun of and

discounted and written off, but again, Madonna warned me about that, so that

wasn't a big deal.

Pete: Well, was there any pressure when it came to recording II? Because I know it came out really quick.

Chris: Yeah, too quick. Lots of pressure from the record label. Our manager Staci Slater, to her, you know, credit, told us to slow down, take some time off, recharge, and get back to our lives for a bit. And we didn't. We bent under the pressure from the record label.

And that was hard.

We were tired. And I always call that record a really great EP, you know.

Somewhere in there is a really great record. Yeah, and the sound is not great.

You know, it's us becoming a real rock ... like the sound of a real rock band,

not the themes of a traditional rock band. But the sound of a ... you know, it

sounds bigger, and it just, again, it's not as interesting to me. You know,

Dinky is way more interesting to me, taking lofty chord progressions and

writing a song to sound like KISS, which is what Mach 5 was, I was just trying

to write a KISS song about my habit of destroying Matchbox cars.

But if you play it

and it sounds like KISS, then there's no joke, you know? But if you play it and

it sounds like Violent Femmes, or our first record, then the joke is intact.

You know, it's just Dinky production of this lost track.

Anyway, so that's

why I think that record falls flat, because we didn't have the self-awareness

to understand what made us work in the first place. We didn't understand this

chemistry of innocence and innuendo, that that's was what was happening. Plus,

I wrote all those songs out of ... I came out of a real dark period in Boston,

but I was also a happy guy. I was a happy guy who had gone through a dark time

with romance and girls and stuff.

And so that first

record was born out of that chemistry. And then the second record comes along

and it's like if a monkey paints a painting with its eyes closed, everyone's

like, "That was brilliant, monkey. Now paint 1000 more of those." And

the monkey's like, "I don't know what I did. I just sloshed some paint

around. I can't do it again."

So, for me, as a

songwriter, there was a lot of weird pressure where I was like, "I don't

understand what I just did. And now I have to do it again. And I can't."

Pete: That answers the next question, if you feel that you've succumbed to the sophomore slump, which it clearly shows that you were.

Chris: Yeah, I mean, we were just following the handbook, man. I mean, we got the brochure. It's like, "Have a lot of success. Sell millions of records. Have a sophomore slump." You know, "Break up. Do other projects. Reunite. Lose a guitar player. Replace him." You know. We were handed a brochure, and we're like, "Okay. We'll just do all the steps."

Pete: So what actually ended up causing the band to break up the first time?

Chris: Just me,

just that conflict between the red flag going up inside me and then the outward

activity of just going ahead and going on tour, and you know, doing the

rigmarole of being in a band on a major label. After a while, the friction

between my real desire and my activities got too much. Plus, I had this voice

in the back of my head that said, "Okay, congratulations on The

Presidents. You did a great job. You're successful in the traditional way, but

this is not your final destination. You have to keep digging. There's some

other voice, some other songs, some other point of view that you haven't found

yet that's really gonna ..." It was like a gut feeling.

So eventually,

that gut feeling got really loud. And I realized, it's like, you can't find the

job you want while you have the job you don't like. Or you can't find the girl

of your dreams while you're dating the one that's just okay. So I was like,

"I gotta quit the band, and zero out, and figure out what this other thing

is."

Pete: So how did everybody come back together a year and a half later and record Freaked Out and Small?

Chris: That was a company called Music Blitz, and they were doing this thing where they were paying bands to record one song that was available nowhere else. And they were gonna make compilation records of these unique songs by known artists. And they were paying good licensing fees for this, and paying for studio time.

So we're like,

"Yeah. We're broken up, but we'll do it. We'll do one." And we did

one, and it was a lot of fun. And at the same time, we did one with ... We had

a band with Sir Mix-a-Lot, called SUbSET.

Pete: Yeah, that was my next question.

Chris: We went in the studio ... We'll get to that, but we went in the studio and recorded a SUbSET song and a Presidents song for this Music Blitz company, and then the Presidents song they liked so much, they're like, "Well, would you guys do a whole album?"

And we're like,

"Well, we're kind of broken up, but sure." Because I had all these

songs that couldn't be played on two and three-string guitars. They needed

six-string and four-string, traditional. So we're like, "Hey, let's do a

traditional record where we play regular instruments."

So we did that,

and that was really fun, really fast, no pressure, 10 days, in and out, totally

... 10 days where we had no songs, and then we just did all the ... like I'd

show up and play an old demo of a song and be like, "Okay, let's do

that." And we'd spend the day tracking, finish it. So we did it really

fast, and Martin Feveyear, our live sound guy, recorded it for us. And that's

when we started working with him. And we worked with him all the way to the

second breakup. So yeah, that album was just a one-off thing. And then we did

one show at his studio that we somehow recorded or broadcast live on the

internet or something. It was our world tour. We're like, "Well, we're not

gonna tour. We're not gonna play shows. But we'll just do this one performance.

And then we'll ... you know call it quits"

And Duff from Guns

and ... Duff McKagan from Guns N' Roses was our bass player for that, because

Dave and I both were playing six-string guitars. And we're like, "Oh,

shoot. We don't have a bass player." So we recruited Duff to play bass.

And he did an amazing job.

I like that

record. It's explosive. I mean, it's really not really what the Presidents

sound like, or what ... but it's ... I don't know. It's another dimension. It's

what we sound like when we're broken up, I guess. That company's gone, and

yeah. So good luck finding that.

Pete: So tell me

about SUbSET. I'd heard about it, but nothing ever came out.

Chris: Nothing ever came out. Sir Mix-a-Lot was approached by somebody who was making a record where they wanted people in Seattle to collaborate to cover Jimi Hendrix songs. So he's like, "Oh, I want to call The Presidents."

So Mix called me

up and was like, "Let's have dinner. And let's talk about something."

And he was very cryptic and mysterious. I was like, "Well, okay." You

get a cryptic phone call from Sir Mix-a-Lot, you probably better follow that

trail of bread crumbs and see where it goes.

So we had dinner,

and immediately we kind of hit it off. It was me and the ... you know, Dave and

Jason, and Mix and his manager Ricardo. And we really just got along great

right from the get-go, and we're like, "Well, forget the Hendrix song.

Let's make up some new songs."

So we went in and

did two or three new songs, and it was super fun, and effortless, and easy, and

great. And then we're like, "Okay. Let's make this into a band. Let's make

a record." And as we worked harder and harder, the common ground

creatively between all of us got smaller and smaller somehow. Mix wanted to

kind of start pushing the music into not just guitar-based drums, but other

stuff. And I was interested in that too, but Dave and Jason were not as

interested in that stuff.

So I called the

band SUbSET because it's like, you know, we have these four personalities that

are pretty different, finding the SUbSET of common ground where we all said,

"Yeah, that sounds great," was what the band was about, kinda. So

that's why we called it SUbSET. But that little ...

Pete: Are there any demos or anything that's floating around that anybody could hear?

Chris: Oh, yeah. They're out there. I mean, I've got a whole album. I've got the album in my iTunes just unfinished with a few songs we never tracked in a studio, but they're live versions. You know, the expectations inside the band and outside the band got really kind of out of control, and I think that project got kind of crushed by its own expectations. And we did a West Coast tour, and it was pretty fun, but it was not profitable.

Yeah. It just sort

of crumbled. And the music is there, but ... And Mix, every once in a while,

I'd see him, and he's like, "We gotta release that SUbSET thing. Just get

it out there." And I'm like, "Yep. Sure. Go ahead. I don't want

anything to do with it because I'm busy with other stuff. But you have my

blessing to finish it." And then nothing happened, so.

But it was on

Napster when Napster was a thing, so it's out there.

Pete: How did you guys come back together and record the Love Everybody record? And what was the reaction when that came out?

Chris: Well, that's Krist Novoselic’s fault, basically. Yeah. For years and years, we had ... you know, for a few years there, we had ... you know, 2000, 2001, 2002, we'd get phone calls like, "Hey, you guys. Will you reunite and play this show or that show?" And we're always like, "Nah. We're good."

But then Krist

Novoselic was gonna get an award for ... not really a Lifetime Achievement

award, but some kind of award for his ... you know, philanthropic efforts or

political action efforts through the National Academy of Recording Arts and

Sciences, or NARAS. They had a big dinner kind of thing, and he was gonna get

an award, and they wanted him to play some songs. And he's like, "I don't

know how I'm gonna play songs." So he called us up and was like,

"Hey, will you guys be my backup band? And when you do it, will you do a

Presidents song and be The Presidents of the United States of America, not just

my three friends?" And we're like, "Yeah. We'll do that."

And all of a

sudden, we looked at each other kind of, we're like, "Yeah. We could be

The Presidents of the United States of America again. Yeah." So that was

gonna be in April of 2003. And we got so excited, we got a rehearsal space and

went in, and started remembering our songs, and did a New Year's Eve show at

the end of 2002 as a reunion show.

And it was

unbelievably fun. I mean, it was like we were the best Presidents cover band

ever. You know? It had been five years, forgot where to put our fingers, forgot

everything, forgot the words, had to re-learn everything, and it was definitely

like learning someone else's songs. You know, the songs had a history, and they

had sort of ... they'd been around, but it was cool. It was not like we made

them up.

So it was like we

got to experience and enjoy the fruits of our labor without feeling all wrapped

up in the ... you know, I don't know, the other part, the business part, you

know? And then slowly, but surely, that kind of turned into an out of town gig

here, and an out of town gig there, and slowly, tenderly, gingerly, we put our

toes in the water. And we're like, "Okay. Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Here we

go. Let's get a manager and start booking shows, get a booking agent." And

then new songs started to pop up, you know.

And we're like,

"Hey, let's make a record." So we did, and all of a sudden, we're

like, "Hey, we're back. Woo hoo." And it was really nice, because we

got to enjoy ... we got to just enjoy it, and not feel any sort of pressure to

prove anything. It was a real treat, and we really got to respect our

achievements without feeling sad.

Pete: What caused Dave to leave the band and Andrew to come in?

Chris: Well, at some point during that Love Everybody, post making the record and touring on it, Dave I think had a similar ... you know, back when I first broke up the band in '98 I went to a band meeting and just said, "Okay, first action item, I quit." And I think Dave felt relief at that point. We had just come back from Australia and things were out of control, like a girl got hurt at one of our shows and had an asthma attack or something and ... I don't know, we started feeling like, a little unsafe.

I mean, nowhere

near of course, you know, I don't know if you've seen that Eight Days A Week,

Ron Howard produced movie about the Beatles' early touring years. They were in

mortal danger all the time. But we felt a little bit of that in Australia, and

things were just a little out of control. So I think Dave was relieved when I

broke up the band the first time, in some ways.

So I think his

threshold for that kind of rigmarole, getting on planes and traveling around

and being away from his family and his little kids, his threshold was way lower

than ... was lower than mine and way lower than Jason's. Jason's Mr. just, you

know, get me to an airport and show me some drums and I'm happy.

So Dave bowed out

because I think he was just like, you know, he saw the future and he was just

like, "Nah, I'm not interested," and now, "I'm not interested

again." So, but Jason and I really were and we loved the record and we

were having fun and really sort of enjoying what was happening. So yeah, we

cast about for another guitar player. The big litmus test for the guitar player

was, will they be okay playing Dune Buggy? 'Cause Dune Buggy was the most kind

of dorky, silly song.

We thought of

people who had kind of a rock pedigree and we're like, "Nah, they wouldn't

play Dune Buggy and ..." so anyway, Yeah, Andrew was a friend of ours. You

know, I shared a practice space with Andrew and shared band members. At one

point I had a side project when the Presidents were broken up, and it was

Andrew's, the rest of Andrew's band, basically, that I was using. So I knew

him.

Yeah, he was like,

"Yeah, I'll do it. I'll try it," and it clicked. So, and he kinda

saved the band and we were with Andrew for another 13 years.

Pete: Okay, so how did you start doing Caspar Babypants, and where did the name come from?

Chris: Well, Caspar Babypants was my stage name when I was with Mark Sandman in the improvisational band called Supergroup, and Yeah, I wore a pair of actual baby's pants on my head. You can find pictures on the ol' internet machine of that.

So I was Caspar

Babypants in that band, and then I forgot about that and then you know, as I'm

paying attention to the little voice in my head that's saying, "Keep

looking for your next thing," I get deeper and deeper in that, and the

music I was making got simpler and simpler and more acoustic and more innocent

and more, you know, like folksy. I was like, "Well, what is this?" Then

I met my second wife, Kate, and her artwork really spoke to me. I was like,

"I wanna make music that comes from that planet, the planet that her

artwork comes from." It's really innocent and simple and well made and

folksy and animals and brights and colors and ...

So I made a couple

songs that were directly inspired by her artwork, and a giant cartoon light

bulb went off over my head. It's like, oh my god this entire time I was

supposed to be making music for little babies. 'Cause they are the ultimate,

you know, enlightened, happy little people. That's the energy I wanna be

around, you know? I'm not cynical. I wanna be like a kid.

So yeah, started

doing it and it clicked, and whereas before with the Presidents I would

struggle to come up with songs, I'm sitting on a creative volcano with Caspar

Babypants. It's like, what is it? Eight years later I've got my 13th record

coming out and no end in sight. So I found the voice. I found the voice that my

inner voice told me to look for, so that's awesome. I'm super happy.

Pete: So how did it feel crowdfunding the last Presidents record?

Chris: I was a little mixed on the crowdfunding thing. Jason was really into it. Jason and this guy Jay Coil that we hired to help us with that project. I kinda went along, I was like, "Yeah, I'll give it a try," and I understood the logic like, you know, people wanna get a thrill out of feeling they're a part of something. I get a little funny asking for money to make a record. Like, I don't know. In this day and age you can buy a laptop and a couple mics and you should be able to get something down, you know. If you can't, then you know, maybe ... I don't know, I don't wanna get into it. Maybe it's ... it's sensitive area.

Feels a little

funny, like people are like, "I need $50000 to make my record," no,

you don't. I've made 13 records on like, three grand worth of gear. You know?

Pete: What caused the final breakup of the band? And is this the definitive break up?

Chris: Yeah, it was different. It was really me. It's me again doing it. I mean, we used to say that we broke up for the same reason Soundgarden did the first time they broke up, that Chris quit.

If your Chris

quits, that's it, you know? So the second time ... the first time was very

passionate and angry. Like I went into the band meeting and I was like,

"First order of business I quit!" You know, just like vomited my

dissatisfaction all over the room.

Second time, very

different. Dispassionate, measured, educated. I found my voice; I had been

doing Caspar and the Presidents for many years. I was like, "Okay,

something's gotta give," and much the same way like when I got divorced

from my first wife, it was ... we worked through all of our issues and we got

to a point where it was just like turning off a light switch and there was no

hot blooded emotions. That has enabled she and I to remain really close and be

great, effective parents for our kids and all this stuff.

So I got the band

in the same spot. I got it to the spot where it was like, "Look, this is

really not the same as the first time," and I did a ton of work on myself

and I figured out this essential thing about myself which is that I'm a fixer.

I tried to fix my mom's sadness by playing music. I tried to fix the world by

singing happy songs. But ... those are positive things, but the negative part

about being a fixer is you can't say no.

Four years earlier

before I broke up the band, I sat Jason and Andrew down and kinda said like,

"Look, I'm really done. Every time I get on a plane from here on out it's

for you guys. Just know that," you know, "The clock's ticking."

So I let four years go by and we made another record. But, and so I thought,

you know, that's a good buffer zone for them to get their stuff together and be

ready. Then I finally just said, you know, "Okay, I'm ready to move

on." It was really easy.

So, and it feels

really appropriate and really good and my plate is beyond full with creativity

and business, running a label and all that with Caspar Babypants and I feel

like I've found my purpose.

Chris: You know what, all I've learned is never say never. That is all I learned. You never know. Highly unlikely though, because ... I don't know. I just can't ... part of it is too, like, you know, you can only sing those songs so many times. I mean, songs really live because they're of a time, you know? Like they're alive because they are you at that moment and they're like a sonic footprint of you.

If you keep

singing them, if you keep singing ones you made up in your 20s when you're in

your 50s, it doesn't fit. It's like, this suit is small and scratchy and I

don't wanna wear it anymore. But I love it, I love it, I'm gonna hang it in the

closet with care. But I can't put it on. So it's just appropriate, you know,

it's ... I think it's inappropriate to keep doing the same thing for your whole

life. I mean, Caspar's gonna end sometime too, probably, and then who knows

what's next.

Pete: What are Jason and Dave up to now? I'm assuming that everybody's still family.

Chris: Yeah, yeah. It's funny, now we're kind of back to the original threesome because we have a never-ending business to run, basically of managing income from the first record, which is the one that makes all the money. So me and Jason now have business meetings a few times a year. We go out for drinks and food and it's like the band is back together in its original form except we don't play any music we just talk about how money moves around.

Yeah, and Andrew's

moved to San Diego, so you know, he's physically not even in Seattle anymore,

so. Yeah.

Pete: But Dave's happier now?

Chris: Dave works at Amazon in the music department. Andrew is doing a bunch of different odd music related stuff. He tour manages a, like Jimi Hendrix hot shot guitar review type show that the Hendrix organization puts on every year. So he's real tight with the Hendrix family and that scene, and gets his ya-yas out on the road by tour managing and traveling and being on tour buses and stuff that he loves. He loves being on the road, that stuff.

Pete: Does Jason still play shows with Love Battery from time to time?

Chris: No, he doesn't. He doesn't play, in fact, last time I saw him he says he hasn't played drums in like, two years and he doesn't miss it.

He doesn't miss

it, I think he kind of maybe came around a little bit to my thinking. Like, all

right, you know, one of the things I said to Jason and Andrew when I finally

broke up the band was like, "Guys, we won. We can stop." Just like

... I don't know if you noticed that we have won the game. So the game's over.

So I think he's

kind of, I feel like from his Instagram and I don't talk to him that much, but

he looks like he's living large and just having a great time just enjoying

life.

Pete: What do you hope the Presidents’ legacy will be?

Chris: I think I hope it'll be just like, a license for ... I hope people will hear it and think like, "Well, if they can do it, I can do it."

I want it to feel

like punk rock in that sense where you know, if these three dorks can pull it

off then I can pull it off. You know who said that actually on the radio one

time, believe it or not, is Andrew WK, remember that guy?

Yeah, he was like,

somebody asked like, "How did you find the inspiration to do this?"

And he's like, "I listened to the Presidents of the United States of

America and I thought, if they can do it, I can do it."

Yeah, the legacy I

would like would be the open-door policy of give it a shot and see what

happens.

Comments

Post a Comment