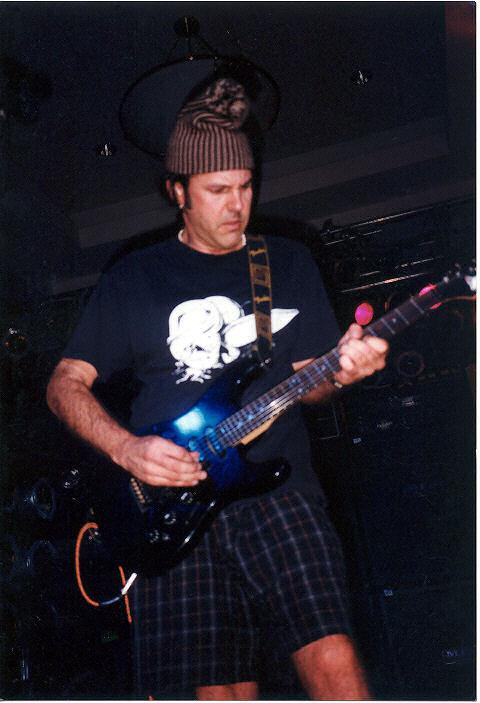

Vapor Trails to the Libido Speedway: An Interview with Jeff Robbins (Orbit)

Discography:

Libido Speedway (A&M, 1997)

Tonedeaf (Lunch Records, 2000)

XLr8r (Lunch Records, 2001)

The Lost Album (A&M, 2011)

Vapor Trails (Lunch Records, 2020)

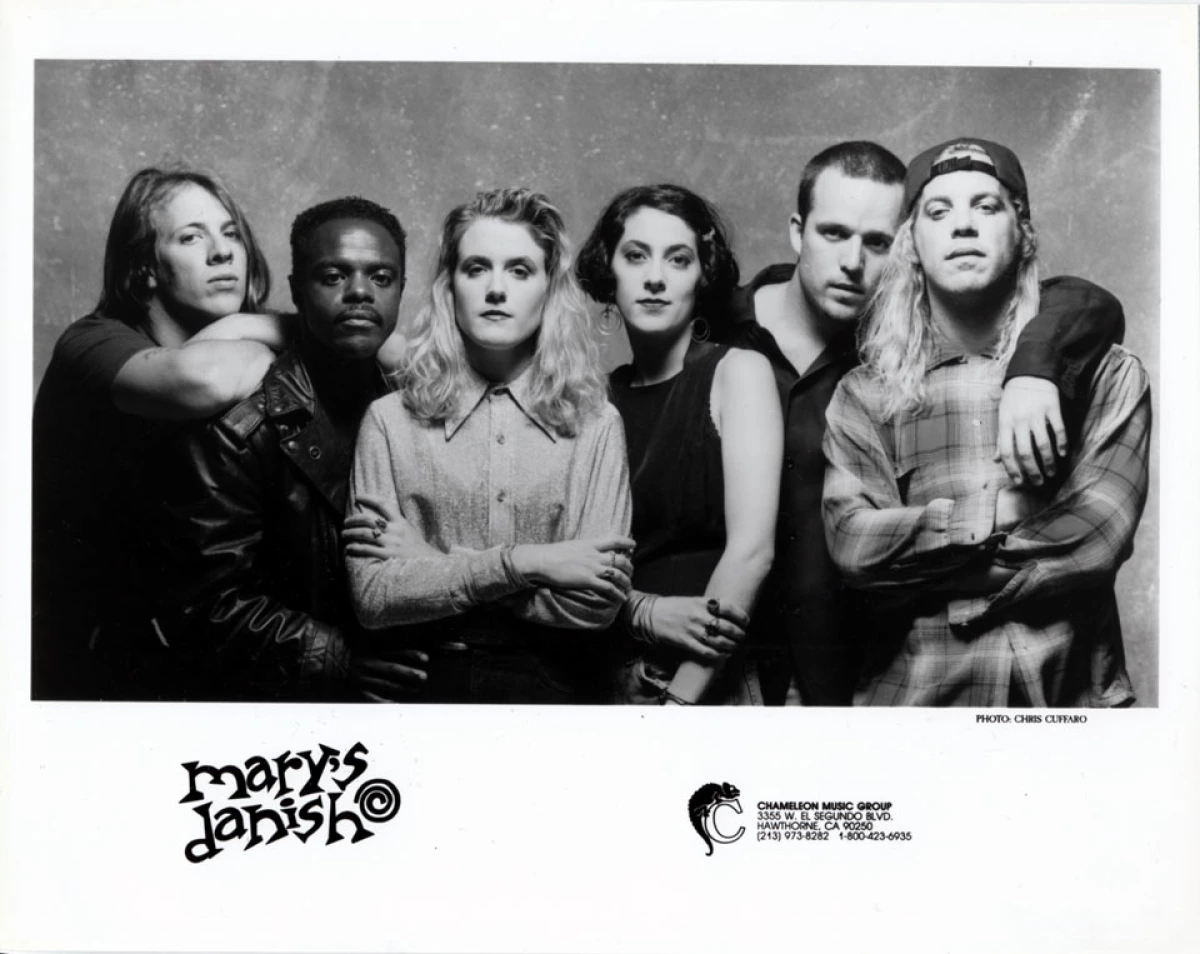

Orbit were a three piece out of Boston that burst onto the modern rock scene in 1997 with their instantly infectious song “Medicine.” The relative success of the song and its album, Libido Speedway allowed the band the chance to tour Lollapalooza ’97, among other opportunities. A second album was shelved when A&M Records was sold and chopped up but the band kept recording, with the help of their own Lunch Records. Subsequent to the band’s hiatus around the early 2000’s, Robbins began a new career as a web developer, something he still does successfully today. Orbit have just released a new-ish album, Vapor Trails, brought together with unearthed tracks from the sessions for their third album. Definitely a band worth checking out.

Pete Crigler: How did you get interested in playing music?

Jeff Robbins: I've always been kind of obsessed with music – more with the sonics and technology than with virtuosity. I started playing the piano when I was young. Then I took up guitar and bass in high school. Back in the 80's I also bought a cassette 4-track, a Roland Juno 60 synth, and a drum machine. That was the beginning of recording, engineering, and producing for me.

Pete: How did the band come together and was the Boston scene helpful for an upcoming band?

Jeff: I had played in several bands in Connecticut where I grew up and then in Boston when I moved there in 1989. But none of the bands quite "clicked."

The Boston music scene was thriving in the early '90's though. I was playing in another band which had been going for a few years, but it was kind of stagnating. I was frustrated. But as I looked around at the Boston scene, I felt like I'd had an epiphany. Energized, I came to my band hoping to try some new things. But they didn't want to change. They had a secret band meeting and decided to kick me out of the band. But we had one more gig booked to play. So they decided to let me know the day after.

The gig was opening for Radiohead at their first-ever show in

the US. They were amazing, by the way – and super nice guys. My band was

walking around like they were at a funeral. Of course, I didn't know what was

going on.

The next day, we got together for another band meeting and they broke the news that they wanted me out of the band. When I finished loading all of my rehearsal gear into my apartment, I went out and bought a new drum machine. I took all of my new ideas and started writing songs. I also started asking around for new musicians to play with. I found (drummer) Paul Buckley through a friend and played him my new demos. He liked them and we decided to start Orbit.

Pete: How would you describe the band's sound?

Jeff: I always liked describing it as "loud music for quiet people." Orbit was rooted as a guitar-based power-trio, but almost more as an architectural decision. I've always liked the dynamics of that format. It's very nimble. There's no distinction between lead and rhythm guitar. When anyone drops out for a moment, a significant thing has happened.

Pete: What was it like

making Libido Speedway?

Jeff: Slow. Boston had a very lo-fi indie-rock esthetic going on. We really liked that sound, but we wanted to try to distinguish ourselves. We chose Ben Grosse to produce. He'd mixed Filter's "Short Bus" album and we were amazed by the sonics of that album. But at the time, Ben was more of a mixer than a producer. He was used to being very meticulous in the studio. So everything took a long time.

Pete: What was the process of writing “Medicine?”

Jeff: I've talked to other musician friends about this. And you rarely know that the hit is going to be a hit when you write it. I was experimenting with the architectural patterns of a three-piece – playing with how the instruments fit into a song. For Medicine, I wanted to write a song where the bass never played on the one beat. Of course, this was a thing that Pixies had done as well. So we ended up feeling like we'd written this Pixies ripoff. Right up until the end, we didn't think it would end up on the album. But of course, it did. And of course, the label picked it as the single. And here we are.

Pete: How did the band come to sign with A&M and do you feel it was a good move?

Jeff: We ended up in a record label bidding war back in 1994. I think we had offers from something like 8 or 10 different record labels offering us deals. A&M was started by Herb Alpert and it still had a reputation as a very artist-friendly label. Soundgarden had just broken through, but they'd put out several albums that hadn't been successful and A&M had stuck with them. We liked that. They were a great label – right up until they got sold to Universal and we got dropped.

Pete: What was 'success' like and how did you react to it?

Jeff: We had a very blue-collar approach to success. The "success" of all that hair-metal shit was only about 4 years old at this point – and the idea of limousines, champagne, and cocaine was not appealing. In retrospect, we probably should have stopped to appreciate some of our achievements. But instead, we just looked at each achievement as a door opening to other opportunities.

Pete: What was it like when Wally left to focus on production?

Jeff: Wally Gagel was the first bass player we asked to join the

band. But he was busy working as an engineer at Fort Apache recording studio

and he was also playing in another band. So we found a bass player named Mark

and did our first EP and the subsequent with him. Then when we went in to

record Libido Speedway, we asked Wally to engineer. Early on in the

recording, we kicked out our bass player. So Wally played bass on a few songs.

I played on a few songs. And we continued asking Wally to join the band – for

the next year while we were recording and waiting to release the album. He

finally said yes, a few months before the album came out.

So we weren't all that surprised when he left near the end of the album cycle. His main focus has always been production. He's been super supportive all along, and we're still friends.

Pete: How was it playing Lollapalooza?

Jeff: It was great! We met a lot of great people from a lot of great bands. We did the whole thing in a van though – and not in a tour bus like most of the other bands. That was a LOT of driving.

Pete: How was it bringing Linda into the band?

Jeff: It was great. It just "clicked" right away with Linda. I think we'd put an ad in the paper looking a bass player and we had auditioned a lot of different people. But I'm pretty sure we called Linda about 10 minutes after she'd left the audition. And we headed out on a tour with her about a week or two later.

Pete: Tell me about the production of the second record and what caused A&M to shelve it?

Jeff: When "Bicycle Song" was released as the second

single from Libido Speedway, it didn't do as well as

"Medicine." So A&M came to us and said, "We want to help you

build a career. Let's not force this new single down anyone's throat. Go in and

record another album and let's start building out a discography."

We decided to get more hands-on and produce the album ourselves

along with Wally. It went much more smoothly than Libido Speedway. We

ended up getting Chris Sheldon to mix. He'd just finished The Colour and the

Shape for Foo Fighters. We mixed it at Dave Stewart's studio in LA and

everyone was happy with the outcome.

However, after we delivered the album to A&M, we started

seeing rumors that the label was going to get sold. It all happened slowly and

without much communication. But in the end, A&M, Geffen, and Interscope had

merged into Universal Records. The accountants came in and if a band hadn't

sold enough albums, they got dropped. Between the 3 labels, about 150 bands got

dropped over a few months.

Because they'd paid for the album – or rather they'd paid for the label that had paid for the album – Universal would not give us the album unless we paid them the entire recording costs. Of course, even if we paid for it, we had no way to distribute it. We shopped it around a bit, but the whole music business had changed. Most labels were focused on finding the next Britney Spears, NSYNC, or Korn. So that's how it ended up getting shelved.

Pete: How did Lunch Records come about and was it easy running a label with Paul?

Jeff: Lunch Records actually started as Breakfast Records around

the time that we started Orbit. We were fed up with being in bands trying to

figure out how to get signed. It's no way to be creative. We figured we'd put

out our own music and find other bands we liked and put out their stuff too. It

was great to feel like we could really execute our creative ideas completely.

Of course, "complete creative ideas" was pretty much what the major

labels were looking for at that time. After a cease-and-desist letter, we

changed the name to Lunch Records, but Paul kept putting out stuff over the

course of Orbit and still continues to put out stuff today.

In fact, it looks like the next full-length from my current band, 123 Astronaut, will be coming out on Lunch Records sometime early next year.

Pete: Was it easy making the Tonedeaf EP and XLR8R record and what caused the band to take a break?

Jeff: No. Not at all. Tonedeaf is actually called that

because we felt so lost and confused. We'd just finished nearly 2 years of

writing, recording, and then waiting for our album to come out – only to get

dropped and lose the album. It looked like no one was going to hear it. How do you

write chapter 3, when you know that no one is going to read chapter 2? Do you

repeat yourself?

But we always knew that at our core, we were self-sufficient. So

we wrote more songs. And we recorded them ourselves. The Tonedeaf EP

came out as a way of testing the waters. Can we do this? Will anyone be

interested? Then we built out the full-length album that is XLR8R. We

had something to prove. It was a marathon. And we finished. But we were

exhausted. When Paul found out that his wife was pregnant with twins, he came

to us and said he needed to step out of the band and find some stability.

Rather than continuing on as Orbit without him, I took it as an opportunity to try something different. Linda and I started a short-lived band called "Well". Orbit guitarist Fred Archambault moved out to Los Angeles to do engineering and production work. Paul got a steady job at a Boston radio station. We all remained friends.

Pete: How did you come to work in web development?

Jeff: I actually started doing web development back in 1992 and 1993 before anyone had heard of The Web. That's what I was doing when Orbit got a record deal. I ran the Orbit and Lunch Records websites through the 1990's and I'd kept up with the technology. Since I'd started so early, I'd become friends with a lot of people who became very successful during the first web boom. I was their cool "rockstar" friend, and they were my cool tech friends. Orbit got dropped around the same time that the tech bubble burst in 2000. So I just sort of jumped off one track and onto the other.

Pete: Tell me about Lullabot.

Jeff: My wife and I ran Ringo Starr's website for a few years.

That led to a lot of opportunities to build bigger and bigger websites.

Blogging had become a thing, but it was hard to find solutions for more

complicated content management on the web. I was searching around and asking

friends for a solution and came across this open-source software called Drupal.

It was free, and it looked really powerful, but it was really hard to use and

there pretty much wasn't any documentation.

As I struggled through my first Drupal project, I found a great

guy named Matt Westgate who lived in Ames, IA. Matt was able to answer all of

my questions and help me with the problems I was having. I kept telling Matt

that if we could start a company that helped make it easier for companies to

use Drupal, we could really have something. We started Lullabot in January of

2006, and by the end of that year we'd built MTV.co.uk,

LifetimeTV.com, and we'd started a big project with Sony Records.

Eventually, we started a long-term relationship with The GRAMMYs, helping them to build out a bunch of websites. In the end, it was my web development career that would bring me to the GRAMMY awards ceremony, not my career as a musician. Go figure!

Pete: What was the process like to get A&M/Universal to release that shelved record and how did it feel when it finally came out?

Jeff: By 2011, the process of releasing a digital album was

basically a push of a button. No record pressing. No CD stamping. No liner note

printing.

Paul ended up with a job producing a video game. Part of his job

was to license music for the game. He had become friends with someone at

Universal – and he convinced him to press that button! ![]()

It's not quite that simple, but it's not too far off from that. The original title of the album was going to be Guide To Better Living – sort of a tongue in cheek title since our lives had been so turned upside down by endless touring and my first marriage had fallen apart. But after getting dropped, we mostly referred to it as The Lost Album, so that's the title we went with when it finally got released.

Pete: How did the reunion come about?

Jeff: We'd been getting back together for various things. We did some reunion shows in 2011 off The Lost Album. We played The Paradise when WFNX closed down. That was the radio station that first took a liking to Orbit. And we played during the closing of the legendary Boston venue TT The Bear's Place.

Pete: What was it like making Vapor Trails; how does the band feel about the record?

Jeff:

We called this one Vapor Trails because it's made up of lost songs and

outtakes from those early-2000's recordings Orbit was doing.

Over the pandemic, I've been playing livestream shows with Orbit songs, 123 Astronaut songs, and Well stuff too. Paul tuned in to some of the early ones and it got him thinking. He started digging through old CDs and DATs and after a little bit of arranging, mixing, and mastering, we ended up putting together an 8-song LP of unreleased tracks.

Pete: What do you hope the band's legacy will be?

Jeff:

Writing and recording songs keeps me sane. Playing guitar and singing is good

for my soul. But it's really nice to know that the music that resonates with me

resonates with other people too. I hope that Orbit, 123 Astronaut, and my other

music will "matter." I don't have a clear threshold for what it means

to "matter" though. Maybe it's more about connecting to people and

not feeling so lonely. It's nice to know that when I write a song, someone is

going to be excited to hear it. Maybe that's what "mattering"

is.

Comments

Post a Comment